Historical writing requires a process of inquiry that includes

- evidence,

- clarity of expression,

- accurate representation of the evidence in sources.

This process of inquiry must be taught explicitly to students through modelling of analytical thinking and guided practice (Grim, Pace & Shopkow, 2004; Okolo et al., 2010).

The following two strategies support students to plan and write history arguments:

- Spontaneous Argumentation (SPAR) debate

- STOP and DARE

Spontaneous Argumentation (SPAR) debate

Spontaneous Argumentation is a discussion-based strategy that

'assists students' understanding of how to effectively use evidence in order to defend their opinion on a historical topic' (Rose, 2013, p.34).

Students must individually construct an argument about a historical topic before engaging in a debate with peers where they must defend their point of view.

Preparation for the activity

Select a historical topic that has different points of view. Create a proposition (or statement) that students will take a position on.

For example:

'Conscription should have been supported in WWI' or 'William Hughes had a significant positive role to play in WWI'.

- Explain the structure and process of a formal debate, discussing terms such as affirmative, negative and proposition in this context. An online recorded video example of debating could be used here as an example.

- Divide students into two groups.

- One side will agree with the proposition.

- One side will disagree with the proposition.

- Students sit next to a peer that supports the same point of view.

- Write the proposition on the board.

- The proposition should relate to a History topic of which students already have some prior knowledge.

- Outline the criteria for evaluation of student participation in the SPAR. These are:

-

Use of information: How well does the student use History content to support their position?

-

Analysis: How well does the student use reasoning and evidence to support their argument?

-

Clash: How well does the student respond to their peer's opposing arguments?

-

Etiquette: How well does the student listen attentively to their peer and politely assert their right to speak?

You might use rank or scale (e.g. 1 = needing improvement to 5 = strongly shown) to help students provide feedback to one another [HITS Strategy 8].

- Provide students with information to support their side of the debate in one of two ways by either:

- Once students have analysed the source that will support their argument, give students 1–2 minutes to write down their arguments and evidence either for or against the proposition.

- Outline the structure that the Spontaneous Argumentation (SPAR) will take place. For example:

- Affirmative opening – 1 minute

- Negative opening – 1 minute

- Unstructured argumentation – 3 minutes

- Negative closing – 1 minute

- Affirmative closing – 1 minute

Note that during the unstructured argument, students should politely but firmly debate their points whiles giving opportunities for peers to do so as well.

- Allocate students to groups of 4 (2 students that support the proposition and 2 students that oppose the proposition).

- For the first round of SPAR, one student that supports the proposition and one student the opposes the proposition will do a debate whilst the other two students listen and watch, taking notes to provide feedback based on the criteria for an evaluation in Step 3.

- These roles are then swapped for the next round of SPAR.

- You might instruct a more confident, knowledgeable pair of students to do the first round of SPAR to model to their peers their approach to the debate in preparation for their turn in the next round. These students could then explain the strategies they used and why they chose them.

- The teacher could then analyse the effective strategies and lead a discussion about what worked well in the modelled debate.

- Provide time at the end of each round for students to provide peer feedback to each other (i.e. 3 minutes). Strategies to promote constructive student talk can be found in

'Talk strategies for group work' and

'Socratic dialogue'.

- Debrief with the whole class at the end of the SPAR activity. Ask students to write their responses to the following prompts before sharing with their peers.

- What did you feel were the strongest arguments for or against the proposition? Explain why you think these arguments were the strongest in the SPAR activity.

- Did you argue a position that you did not agree with? What might be a benefit of arguing for a position that you might not necessarily agree with?

- What did you learn from doing the SPAR activity that might help you to write arguments in History in the future?

(Adapted from Rose, 2013; IDEA, 2004, Snider & Schnurer, 2002)

Links to the curriculum:

VCHHC104,

VCCHC101,

VCHHC125,

VCHHC128,

VCHHK139,

VCHHK142,

VCHHK144.

STOP and DARE

The STOP and DARE strategy is a useful acronym that helps focus student attention on key actions that they should take in planning to write an argument piece in History (De La Paz, 2005).

'STOP' prompts students to create both sides of an argument before they select a position to take. It stands for:

-

Suspend judgement

-

Take a side

-

Organise

-

Plan as you write

'DARE' prompts students to remember the key elements of a sound argumentative essay and the importance of considering the reader's perspective. It stands for:

-

Develop a topic sentence

-

Add supporting ideas

-

Reject an argument for the opposing side

-

End with a conclusion

Preparation for 'STOP' and 'DARE'

Ensure that students have access to relevant historical sources and their class notes to help them with their History argument.

You might also wish to do other activities before using 'STOP' and 'DARE' to write a History argument, such as a 'Spontaneous Argumentation (SPAR) debate'.

- Give students a topic.

For example,

The Environment Movement. - Provide an event (or choice of events) in relation to the topic.

For example,

damming of Australia's Gordon River or the Jabiluka mine controversy in 1998. Ask students to begin with the STOP steps. Instruct them to:

Suspend judgement

Brainstorm all the issues that might have created disagreement between different groups

For example, the Australian government, an environmental interest group(s), an energy company.

Take a side

Choose a point of view relating to the event.

For example, an environmental interest group.

Organise

Organise information from sources to analyse and include an opposing argument

Plan and you write

Write details to support their viewpoint.

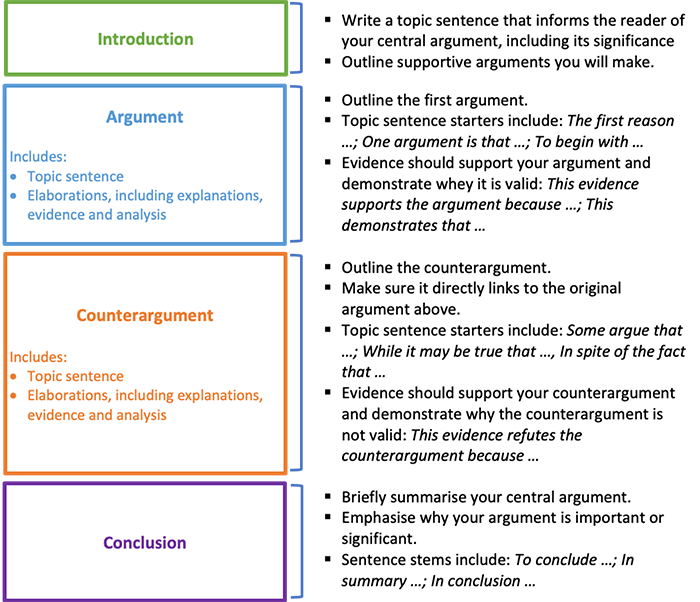

- Ask students to begin writing their response by going through the DARE steps and using a template like the one below. To compose their response, instruct students to:

Develop the topic sentence

Identify the main idea such as:

'Australia's natural environment has always been susceptible to threats from people and it is right that places like Australia's Gordon River are protected for future generations.'

Adding supporting ideas

Students begin writing, making their case

Reject an argument for the opposing side

Students address counterarguments

End with a conclusion

sum up their position to close their response

Provide students with a framework to support them to write their response, like the one below.

- Once students have written a draft of their response, ask them to swap their response with a peer. Instruct students to provide feedback on:

- Strengths in their peer's argument. For example

- clear statement of contention;

- valid evidence used to support contention;

- persuasive rejection of counterargument supported by strong evidence drawn from source(s)

- Areas for improvement in their peer's argument, for example,

- contention not linked strongly enough to the focus area or the point of view taken;

- counterargument does not relate explicitly to the initial argument made;

- evidence is missing, not quoted/cited properly or not valid enough;

- counterargument seems more persuasive than an argument for own point of view

Links to the curriculum:

VCHHC099,

VCHHC100,

VCHHC102,

VCHHC123,

VCHHC125,

VCHHK159,

VCHHK160.