When students engage with a historical source, they need to be able to answer the following questions:

- What is the source about?

- How has the author structured and presented the text, images, sound, etc. in the source to portray information?

- Why might the author have made certain choices in the way that they structured or presented the source?

The following strategies support students to consider the above points when they read, interpret and analyse history sources:

- Reading and paraphrasing wrote sources by chunking

- Interpreting visual sources by cropping

- Analysing sources through questioning

Reading and paraphrasing by chunking

Chunking involves breaking down a complex historical text into more manageable parts to enable students to make meaning of what they are reading. Students then summarise what they have read in their own words.

Chunking

- enables students to demonstrate their understanding of a historical source

- enhance students' ability to paraphrase

- supports students to organise and synthesize information from the source that they are focusing on.

The steps below outline how to chunk a complex written historical text.

- Select a historical text for students to read and chunk. For instance,

- a paragraph in a textbook can be chunked into phrases and sentences

- a reading of a couple of pages, such as a letter or document, can be chunked into paragraphs or sections.

If this is the first time that students have chunked a complex text, teachers might wish to show students a worked example [HITS Strategy 4] of chunking using a simpler text.

- Before students read the historical text, ask them to skim the text and do the following:

- highlight unfamiliar words

- read the words and sentences around the unfamiliar words to help define unfamiliar words

- lookup the meaning of unknown words

- write a synonym for the newly defined unfamiliar terms and annotate this beside the term(s)

- circle important historical people, places or events related to the main topic of the text

- encourage students to look at the heading and/or sub-headings in the text to identify what the main topic is

- re-read the text to make sure that the above steps have been completed appropriately.

- Ask students to 'chunk' the text. Chunking involves breaking down complex texts into sections to enable reading and understanding. Students look for keywords, ideas and themes in the text. When the text has been broken down into chunks students organise and synthesise information then paraphrase. The process of writing in one's own words helps to expand vocabulary and demonstrates an understanding of the content of the text.

To support students, provide a table as a structure for chunking the text. Tables enable students to see important 'chunks' of text in the form of a visual organiser. Each column of the table has a heading such as a participant, action, aim, reason and impact. As students dissect the text they identify and record relevant sections for key themes. An example of a 'participant structure' for sentence chunking is shown below with the associated text.

- Ask students to rewrite 'chunks' in their own words.

- Instruct students to share their paraphrased version with a partner. In pairs, students discuss:

- What is similar about their paraphrased versions?

- What is different about their paraphrased versions?

- Looking at both versions, which version better reflects the meaning in the original text? Why?

- As students discuss together, they each annotate their own paraphrased version and write questions they may think of as a result of discussing the text with their partner.

- Share responses to the reflection questions as a class.

- As a class discuss new questions which have arisen from the paired discussion.

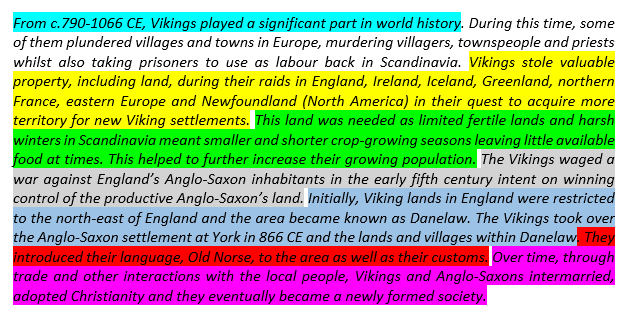

Example of chunking in a Year 7 or 8 class learning about Vikings

The 'participant structure' chunking table has been adapted from Schleppegrell, Greer & Taylor (2008, p. 180) (VCHHC103,

VCHHK116,

VCHHK117,

VCHHK118,

VCHHK119,

VCHHK120).

Original text

From c.790-1066 CE, Vikings played a significant part in world history. During this time, some of them plundered villages and towns in Europe, murdering villagers, townspeople and priests whilst also taking prisoners to use as labour back in Scandinavia. Vikings stole valuable property, including land, during their raids in England, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, northern France, eastern Europe and Newfoundland (North America) in their quest to acquire more territory for new Viking settlements. This land was needed as limited fertile lands and harsh winters in Scandinavia meant smaller and shorter crop-growing seasons leaving little available food at times. This helped to further increase their growing population. The Vikings waged a war against England's Anglo-Saxon inhabitants in the early fifth century intent on winning control of the productive Anglo-Saxon land. Initially, Viking lands in England were restricted to the north-east of England and the area became known as Danelaw. The Vikings took over the Anglo-Saxon settlement at York in 866 CE and the lands and villages within Danelaw. They introduced their language, Old Norse, to the area as well as their customs. Over time, through trade and other interactions with the local people, Vikings and Anglo-Saxons intermarried, adopted Christianity and eventually became a newly formed society.

|

The Vikings |

stole property |

to grow more crops throughout the year |

to feed their people |

population increased |

|

The Vikings |

Raided England |

to win control of Anglo-Saxon land |

to develop settlements where farming and trade were more productive |

a new society was created between Vikings and Anglo-Saxons (e.g. religion, language) |

(Adapted from Schleppegrell, Greer & Taylor, 2008, p. 180)

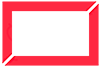

Interpreting images by cropping

Cropping helps students to focus their attention on parts of a visual image (e.g. photograph, illustration). It encourages students to notice portions of an image that they might otherwise have overlooked and to identify and respond to each portion before they try to interpret and analyse the overall meaning of the image.

The steps below outline how to crop a complex historical image (e.g. photograph, illustration).

Preparation for cropping

- Select an image that students will analyse. Make a copy for each student or pair of students.

- Provide students with a blank A4 sheet to make cropping tools. Ask students to cut two L-shaped pieces from the A4 sheet as shown below.

- Distribute a copy of the image to students.

- As you ask each question prompt to support students to analyse the image, instruct them to:

- Use the two L-shaped strips of paper to create a rectangle shape around the part of the image they are focusing on in response to the prompt by moving the two pieces together, or further apart, to highlight a smaller, or larger, part of the visual source respectively.

- Think about their response to the prompt silently for 1 minute.

- Share their response with a partner for 2 minutes.

- Write a response to the prompt in 3 minutes based on their thinking and their discussion with their partner.

For example, students may focus on the following three sections of the montage of World War 1 images below.

- The following are examples of prompts that you might ask students as they view parts of the image.

- Some of the questions lead students directly to parts of the images (for example, are more closed-ended)

- others provide scope for students to investigate parts of the image of their own choice (i.e. they are more open-ended).

| Focus on the part of the image that... |

Focus on the part of the image that... |

Shows a specific named person/location/action/event/period in history.

- Describe him/her/it/them.

|

First caught your eye.

- Explain why you selected this part of the image.

|

Shows words.

- State what the words refer to.

|

Best describes what the source is trying to portray (or communicate).

- Outline the main message of the source.

|

| Shows a problem/tension/controversy/particular perspective.

|

Shows a person/location/event that you do not know about.

- Explain who you think the person/location/event might be.

- Why do you believe this to be the case?

|

Examples of responses to prompts for the image below, used in a Year 9 or 10 class learning about World War I (VCHHC123,

VCHHK141,

VCHHK142), might be:

Prompt 1: Focus on the part of the image that first caught your eye. Explain why you selected this part of the image.

I selected the symbol on the tail of the plane (1) as the contrast of the dark symbol on the light background is striking. It identifies the aircraft as German warplanes and would make them highly visible in combat.

Prompt 2: Focus on the part of the image that shows a specific thing used in WW1 warfare. Describe it.

The gas mask (2) in the image seems to be an earlier version of more modern ones. It might have helped protect these two soldiers from chemical weapons like mustard gas.

Prompt 3: Focus on the part of the image that best describes what the source is trying to communicate. Outline the main message of the source.

This part of the image shows blackened earth, dead trees and what look like the remains of buildings or machines (3). I believe that this part of the source image is trying to show the devastation of war on humanity as well as the environment.

Analysing sources through questioning

Analysing primary and secondary sources can be challenging for students as they require the skills to:

- read, view or listen to the source and take meaning from it

- recognise and understand the social and cultural context of the production of the source

- appreciate how opinions, values and ideas might influence what they read, see or listen to in the source

- evaluate whether the source is a credible, reliable and valid representation of the past (Roberts, 2013, p. 21).

Questioning is a high impact teaching strategy [HITS Strategy 7] and source-dependent questions can be useful in focusing student attention so that they can:

- identify history-specific information in a source

- extracting meaning from the source

- critically analysing the intent of this information (Gabriel, Wenz & Dostal, 2016).

Literacy in Practice Video: History - Interpretation And Analysis

In this video, the teacher uses a visual image of a historical document for students to analyse and interpret using key questions to guide deeper of the artefact.

Read the in-depth notes for this video Types of questioning

Teachers can use three different types of questions to support students to analyse sources they read: literal, inferential and evaluative.

Literal questions

Literal questions ask about facts that are explicitly stated in the source.

For example:

-

Who was the source created by?

-

What do you know about them? (Consider age, gender, social position, occupation, religious beliefs, etc.)

-

When was the document written?

-

What was happening at the time? (Consider significant events, political environment, common prejudices, social norms, etc.)

Inferential questions

Inferential questions require students to

- analyse and interpret specific parts of the text

- 'read between the lines' of what is explicitly stated

- infer the purpose of the creation of the source.

Students should draw on their prior knowledge, practical experiences and evidence from the source to support their responses.

For example:

- 'Why do you think that (an individual or group portrayed in a source) acted in a particular way? Explain your reasoning.'

- 'Why did the creator of the source produce it? (Consider whether it was to make money, influence people, tell their side of the story, record an event, criticise someone, etc.)

- 'Who might have been the intended audience for the source? How do you think the creator wanted the audience to respond? List evidence from the source and your knowledge about the creator that led you to your conclusion.

Evaluative questions

require students to use their knowledge, values and experiences to

- decide whether they agree with the author's ideas or point of view expressed in the source

- determine if the source is reliable, credible and valid.

For example:

- 'Does the source show any bias? Is the creator of the source trying to present only one of many perspectives? What words/ phrases suggest bias?'

- 'Are there any parts of the source that seem to be inaccurate? Describe these and explain why you believe these parts are inaccurate.'

- 'Does the source that you are looking at support, or contradict, another source that you have looked at previously? What is this other source? In what ways do the sources contradict each other?'

(Some questions adapted from Morris & Stewart-Dore, 1984;

)

Examples of questioning

A Year 9 or 10 class learning about Rights and freedoms (1945–the present) might be asked to analyse

Separation: Ruth's Story. Some questions teachers might use when students read

Ruth's Story might be:

Literal Questions

For Ruth's story:

- Who was Ruth's story created by?

- What do you know about her?

For the extracts from Read's report:

- When were the document extracts written?

- What was happening at the time that the document extracts were written?

Inferential questions

For Ruth's story:

- why do you think that she acted in the way she did at the mission?

- explain your reasoning.

For the extracts from Read's report:

- what do you think were the motives behind the actions taken by the Aboriginal Welfare Board at the time that the source was written?

- what makes you say that?

Evaluative questions

For Ruth's story:

- is there any bias shown?

- Is the creator of the source trying to present only one of many perspectives?

For the extracts from Read's report:

- what do you think is the purpose of the source?

- Outline the parts of the source that suggest that this is the purpose.

Additional notes

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students should be advised that these sources may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

A useful resource to provide some

background information on the Stolen Generations can be found on the Racism No Way website.

Links to curriculum:

VCHHC123,

VCHHC124,

VCHHC125,

VCHHK152,

VCHHK154,

VCHHK156.

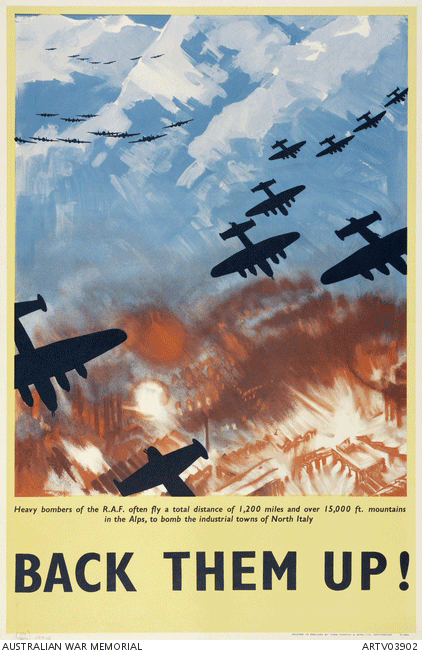

Interrogating the data source

Students need to be made aware that historical data and figures that are referenced (for example, in a news article) might have been taken out of their source or is decontextualized. When data is decontextualized, it might not accurately or reliably express the intent of the individual or organisation that originally produced the data. For instance, the individual or organisation that originally produced the data might have done so to inform government policy (e.g. the ABS) but the individual who has authored the news article might be doing so to persuade the public to support a stance on a given social or political issue.

To support students to interrogate a data source, teachers can:

- Provide students with a source that contains historical data, such as a table, chart, graph, news article, cartoon or poster. For example, the poster below (Accession Number ARTV03902 in the Australian War Memorial collection.)

- In pairs, instruct students to interrogate the source using the prompting questions below:

- Is the source credible (i.e. produced by a reputable organisation such as a government department)?

- Does the source show any bias? In other words, is the creator of the source trying to present only one of many perspectives on the historical topic?

- Are there any parts of the source that seem to be inaccurate? For example, are there things you would expect to see in the source which is not depicted? Do certain numbers in a chart, table or graph seem especially small or large?

- Does the current source support, or contradict, another source that you have looked at? What is this other source? In what ways do the sources contradict each other?

- Share student responses as a class.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCHHC123,

VCHHC124,

VCHHC125

Developing a double-entry journal with text-dependent questions

Students can keep a double-entry journal about historical texts they read, such as textbooks, news articles, documentaries, primary sources, reports and Internet sources). A double-entry journal is like a reading log, in which students record their observations, impressions and theories related to history texts as they read (Marsh & Hart, 2011).

As the name suggests, a double journal entry log requires students to record two types of data: an objective summary and a subjective reflection. The table below suggests how students might set up their journals. Each column is one page of a two-page spread.

|

Author and publication details |

Your general thoughts on the overall content of the reading |

|

Five sentences summarising main points

or

Five text-dependent questions

|

Do you agree or disagree with the five main points? Give reasons.

or

What further thoughts do you have about the answers to the five text-dependent questions?

|

|

Four key quotations |

Explain why you have selected each quote |

|

One student-developed question about the text |

Why do you think this question is important? |

When students first begin using a double-entry journal, teachers can support them by providing text-dependent questions or demonstrating how students can generate their own text-dependent questions (see

'Generating text-dependent questions' in Science).

Questioning is a high impact teaching strategy [HITS Strategy 7] and text-dependent questions can be useful in focusing student attention so that they can identify key discipline-specific information in a text as well as extracting meaning from, and critically analysing the intent of this information (Gabriel, Wenz & Dostal, 2016).

The following text-dependent questions can be given to students before reading. The questions have been grouped for: primary sources, secondary sources, and personal responses.

Questions for primary sources

- Who is the author of this text?

- What do you know about them? (Consider age, gender, social position, religion, etc.)

- What are their thoughts, opinions or viewpoint on the historical event?

- What biases do they have?

Questions for secondary sources

- What is the historical event/situation/issue being discussed/analysed/evaluated?

- When and where did the historical event take place?

- Who are the key players/stakeholders involved?

- What did these key players/stakeholders do in this situation/problem/issue?

- Is the problem ongoing? What are the ongoing issues? How does the historical event impact today's society?

- Are there any other possible opinions or viewpoints on this historical situation/problem/issue? Are these expressed in the text and, if so, what are they?'

Personal response questions

- 'What did you read in the text that might have influenced your opinion or viewpoint on the historical event? (For example, evidence-based on data or expert opinion.)

- 'What have I learned about the historical event by reading this text?'

- 'What do I still need to learn about that historical event to understand this text better?'

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCHHC123,

VCHHC124,

VCHHC125