When students communicate their understanding of History, they need to be able to

- sequence chronology

- analyse cause and effect

- identify continuity and change.

Students might oversimplify their responses by only listing different outcomes to a variety of events without clearly explaining how the events relate to each other (Manning, 2006, p. 189). By encouraging students to actively represent and communicate their History knowledge in different modes (i.e. written, visual and spoken), teachers can help students to better describe and explain historical concepts.

Three strategies to support students to represent their understanding of History in multimodal forms are:

- Sentence stems with conjunctions

- Sentence expansion grid

- Creating an annotated timeline.

Writing explanations using conjunction sentence stems

Historical explanations explain past events by discussing and examining the causes and consequences relating to that event (Coffin, 1997; Schleppegrell 2004, 127). The two common types of explanations used in history are factorial explanations and consequential explanations.

A

factorial explanation explains the various factors or reasons that contribute to a phenomenon, situation, event or outcome. Common conjunctions used include, as a result of, another reason for, since, when, even though.

A

consequential explanation explains the ramifications or effects of a phenomenon, situation or event. Common conjunctions used include, although, another consequence of, since, such as, due to.

(Adapted from Coffin, 2006, p. 75).

Explanations of factors that contribute to historical events and discussions of the consequences of these events are logically sequenced in sentences using conjunctions such as, for example, because, since and although. (Coffin, 1997; Schleppegrell 2004, p. 127).

Using sentence stems which include conjunctions can support students to craft more complex explanations and to develop their capacity to understand such explanations when they see them in their reading.

- Explicitly state to students:

- the learning intention: To improve the quality of their written explanations in history

- success criteria: use appropriate sentence stems and conjunctions to show sequence/cause/effect/consequence [HITS Strategy 1]

- Lead a class discussion to jointly construct definitions for:

- factorial explanation

- consequential explanation.

- Explain the meaning of the conjunctions that students will use for this strategy. The table below describes the two kinds of explanations and outlines some common conjunctions that are used for each.

Note: Several other conjunctions can be used when writing explanations, including: -

Time, for example: after, before, when, while, as, since, until, whenever

-

Manner, for example: by, through, with, as if, as though, as, like

-

Cause, for example: as, because, since, as a result of, in order to, in order that

-

Condition, for example: if, as long as, unless, on condition that

-

Concession, for example: although, even though, while, whereas, despite

Other strategies to support students to read and write explanations can be found in

the Science section and the

Economics and Business section of the toolkit.

- When using sentence stems with conjunctions, teachers may provide models of worked examples [HITS Strategy 4] with a simple sentence stem that is not related to history content to show how the conjunctions affect the response provided. For example

-

When the student arrived in class, the teacher asked her why she was late.

-

Although the student was late, she did not get into trouble.

- This was the fifth time the student was late to class,

so she received detention after school.

- Ask students to read, view or listen to a selected historical source (e.g. textbook extract). Teachers can provide students with a range of sentence stems with conjunctions that have been modelled to support them to write explanations. For example,

-

When the Black Death spread across the world …

-

Although many people died during the Black Death, …

-

Many people died during the Black Death, so …

- Share different students' responses to each sentence stem as a class to check that students can not only demonstrate their historical knowledge and understanding but also distinguish between different types of explanations.

Links to the curriculum:

VCHHK111,

VCHHK112,

VCHHC103.

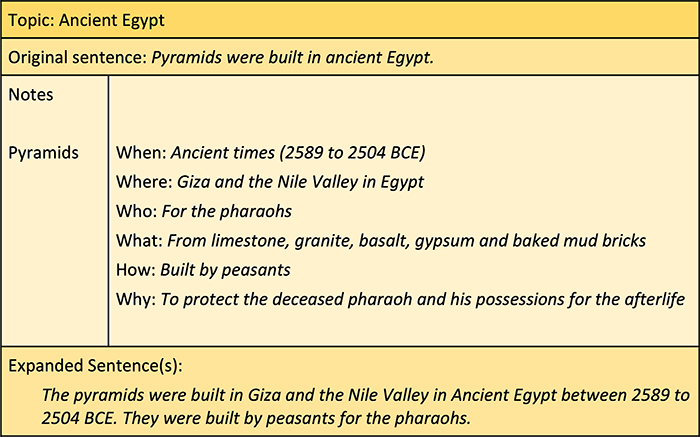

Sentence expansion grid

Students might be asked to write descriptive historical texts such as biographical or historical recounts and reports. Whilst it is important for students to recognise the importance of including detail in their descriptions, they also need to be mindful of discerning which pieces of information are more relevant to include in their descriptions.

The following strategy helps support students to

- focus their attention

- structure their written response on key details in a description.

The sentence expansion grid can also be used for general note-taking when reading secondary sources and shows some similarity to

the Cornell notetaking system, which is outlined in the Science section of the Toolkit.

- Provide students with a Sentence Expansion grid template (see below).

- As students read, view or listen to a historical source, they write down any significant people, events or details in the 'Notes' column. They should use bullet points for this. There should be one idea per cell, for example, pyramids, pharaohs, gods.

- Students read, view or listen to the text a second time. As they do, they answer question prompts in the sentence expansion section. For example, teachers might use the 5W&H (who, what, where, when, why and how).

- Once students have answered all the prompts, they use their answers to create a sentence that expands on the original simple sentence at the top of the grid.

(Adapted from Hochman & Wexler, 2017, p.60)

- Students share their responses in pairs or small groups. Alternatively, the teacher could ask two or three students to write their expanded sentences on the board.

- Students compare their sentences [HITS Strategy 9] by considering the following questions:

-

'What information did this student include in their expanded sentence(s)? What information did they exclude in their expanded sentence(s)?'

-

'What types of language techniques did they use to expand their sentence(s), e.g. conjunctions or use of specific terminology? Provide an example of where you see this being used in the sentence(s).'

-

'What similarities are there between this student's expanded sentence(s) and mine? For instance, many expanded sentences will probably start by stating a time or a place.

- Teachers may explicitly discuss why descriptions in History usually start with time or place, to help students understand that these sentence starters help to situate the historical person or event in a context.

Links to the curriculum:

VCHHKK111,

VCHHC099.

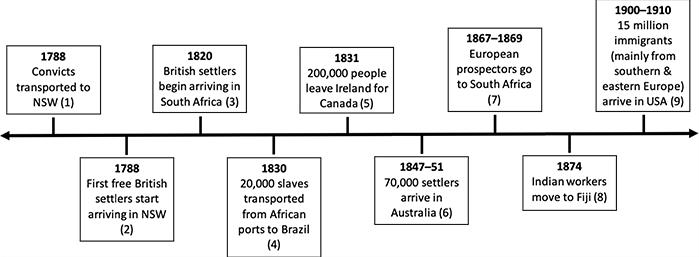

Creating an annotated timeline

Timelines are a meaningful narrative of the past. They support students to grasp the scale of changes over time in History (Dawson, 2004).

In History, timelines provide a way of communicating the relative occurrence and sequence of events through the visual representation of a chronology. Timelines can be:

- comparative: representing events across different cultures and geographical contexts,

- correlative: representing corresponding or mutual events that occurred at a time.

Timelines can enable an understanding of significant periods in historical time and contextualise specific historical eras (e.g. Victorian age, Middle Ages, Renaissance). Knowledge of chronological time and relative occurrence of events is critical for historical understanding.

There are several literacy demands in the production and interpretation of timelines:

- Timelines are multimodal.

- The spatial organisation of information (both written language and visual) is fundamental to meaning-making.

- Timelines involve reading text and numbers and require an understanding of the

- significance of linear visual representation

- meaning of discipline-specific terminology and abbreviations (e.g. BCE, CE).

Having students add annotations to timelines encourages them to explain the connection between events and specific global processes. The following are steps to create an annotated timeline:

Preparation for the annotated timeline

Select a time period (or more than one time period) to focus on and a historical theme that is relevant to world history. For example

- cultural

- demographic

- economic

- environmental

- political

- social.

Select 8–10 key events that are related to the time period and the theme. Prepare a template of a timeline for students to use. Alternatively, students could use the

Timeline Tool on Fuse.

- If introducing the annotated timeline for the first time to the class, provide a worked example [HITS Strategy 4]. This can be done by

- modelling the example below on the board (i.e. using a handwritten or projected completed timeline) or

- distributing one key event written on a sheet of paper to specific students in the class and asking them to place it on the board in order and position on the timeline.

- asking students to come up to the front of the class and stand in position showing the rest of the class the event of their sheet of paper before transcribing this on the board.

Time period(s), themes and a template of a timeline should be given to students the first time they complete their own annotated timeline. As students become more familiar with the strategy, you might provide them with the time period(s) and the theme but ask students to identify the 8 – 10 key events that are related to these.

-

Distribute the copy of the template timeline.

- State the theme.

- For example,

The movement of people during the Industrial Revolution period.

- Ask students to note each event on their timeline, see example below. Each event should be clearly labelled and numbered in chronological order on the timeline.

- Below the timeline, instruct students to write one annotation for each event.

- The annotations should be numbered as per the timeline.

- Each annotation should explain why the event was important or significant to the theme.

For example,

what were the reasons why people moved?

- To assist students with their annotations, encourage them to

- Once students have completed their 8–10 annotations, ask them to write a summary statement.

- The summary statement should cover how the 8–10 events relating to the theme in the time period(s) show change and continuity.

- As a class, share the summary statements to compare responses. This could be done in several ways. Students could verbally share in pairs or small groups, they could swap statements and silently read each other's statement, they could display statements on a wall or electronically through a shared space.

- Ask students:

'What is similar and different about the students' summary statements?'

- After students have heard one another's summary statements, ask them to reflect on their own.

- Instruct students to ask themselves:

-

'Does my summary statement show change and continuity over time in world history?'

-

'How can I improve my summary statement?'

- Ask students to make changes to their summary statement based on their peer's summary statements and their responses to the self-reflection questions [HITS Strategy 9].

(Adapted from Anderson et al., 2012, p. 13).

Annotations: What was the reason why people moved?

-

British transported individuals convicted of a crime as punishment to Australia.

-

Free settlers arrive in Australia to seek better lives for themselves and their families.

-

Poor conditions at home convinced British people to go to South Africa seeking opportunities with encouragement from the Cape Government who wanted to boost its English-speaking population.

-

People were persecuted and sent away to be used as slave labour to produce sugar, tobacco, cotton and coffee, for instance, in places such as North America and the Caribbean.

-

Famine and starvation pushed many to leave Ireland for a better life.

-

The discovery of rich deposits of gold encouraged individuals from places such as China to become prospectors in Australia.

-

The discovery of diamonds and gold encouraged prospectors to seek riches and wealth in South Africa.

-

With strong demand for labour on sugarcane farms, Indian workers went to Fiji to seek opportunities to earn money as farm labourers.

-

People came to the USA escaping racial, religious or political persecution. Others came trying to find economic opportunities. Some were recruited to go to the USA by contract agreements to provide their labour in the USA.

Summary statement

Many people moved from the Old World (e.g. countries in Europe) to the New World (e.g. Australia, America) during the period of the Industrial Revolution. Some left the land of their birth because of poverty, punishment or persecution that they experienced at home. Some were encouraged to move to new countries because of opportunities they saw to improve their way of life.

Links to curriculum:

VCHHC097,

VCHHC098,

VCHHC121,

VCHHC122,

VCHHK130,

VCHHK132.