Conceptual vocabulary development (reading and viewing)

Learning in English often includes conceptual language. This language tends to be abstract: it can relate to themes or content contained in the target text or be metalanguage (language about language) associated with literary analysis.

For example, students involved in the study of news media are likely to come across abstract language found in news articles (revolution, government, justice, legality, human rights, multicultural). At the same time, the teacher may introduce unfamiliar language that relates to the analysis of the media reporting (tone, alliterative, stress, trope, rhythm, rhetorical).

Creating synonyms and antonyms

Learning about the meaning and spelling of words happens best in the context of authentic reading or writing experiences (Adoniou, 2016). Munro (2002) suggests that teachers should use explicit instruction to develop student understanding and confidence with new vocabulary:

- Teach the class how to say the words accurately.

- Ask students to read the written iterations of the words.

- Provide time to practise spelling these words—this can include building deeper understanding of how the word is ‘put together’ (see example below).

- Support the creation of synonyms and antonyms for each word.

- For example, when Year 8 students are studying ‘Broken Toys’ from Tales from Outer Suburbia (Tan, 2008), exploration of the word ‘stealthily’ might involve listing the following synonyms: quietly, sneakily, silently, inconspicuously; and antonyms: noisily, conspicuously, obviously, clumsily.

- Clarify the meaning of each term and link it with other concepts.

Using word matrices

The following word matrix (adapted from Peter Bowers,

WordWorks Literacy Centre) is an example of how the root words, suffixes and prefixes of a word (in this case, ‘unmoved’) can be broken down with students.

Word matrices example using the word - 'unmoved'- showing how root words, suffixes and prefixes of a word can be broken down with students.

| re | move | al |

| ed |

| s |

| un | ing |

| er |

| ment |

Teaching metalanguage in context

Parkin & Harper (2019) describe building students’ understanding of increasingly sophisticated vocabulary through ‘powering up and powering down’. They provide the following example of an interaction that develops student understanding of metalanguage through a study of Paul Jennings’s ‘Nails’ (1990):

Teacher

That’s right. He’s giving us a clue – isn’t he? – that the resolution has something to do with the sea.

Now here’s a new word for you today. All those little clues that Paul Jennings gave us are called ‘foreshadowing’. (Writes on board.) Foreshadowing. They’re like the shadow of what is to come.

If you hid around the corner with the sun behind you, I wouldn’t be able to see you, but I might see your shadow, so I would know that a person was there. Let’s say that word together.

Student

Foreshadowing

Teacher

And what is that again?

Student

When the author gives us a clue about what’s coming in the story.

By ‘powering down’ into everyday explanations for a new term (“the shadow of what is to come”) and then back up again into the technical term (“Let’s say that word together: foreshadowing”); students’ understanding of new vocabulary is being built in the course of classroom dialogue around the text.

This strategy supports students to work conceptually and to engage in discussion about abstract ideas (VCELY395,

VCELA473).

Connecting grammar and the text being studied (reading and viewing)

Grammar is the set of structural rules that govern how words are put together to construct a text. While the fundamental rules of grammar are consistent, each genre of writing will often employ only a subset of these rules. To write effectively, students need to understand the grammatical features of a given text type and genre.

Myhill (2018, p. 12) describes four key principles for the teaching of grammar, LEAD:

-

L - Make a link between the grammar being introduced and how it works in the writing being taught.

-

E - Use grammatical terms but explain the

grammar through examples, not lengthy explanations.

-

A – Use examples from

authentic texts to link student writers to the broader community of writers.

-

D - Build in

high-quality discussion about grammar and its effects.

Myhill’s resources for teachers in practice

Myhill’s

Resources for Teachers demonstrates how teachers can address and embed each of these principles in their lessons. Here, we focus on the first principle and provide illustrations of aspects of grammar that teachers can connect to the text being studied - Amber Kwaymullina and Ezekiel Kwaymullina’s 'Catching Teller Crow' (2019).

- In the first chapter, the authors use two different

expanded noun groups to describe the character’s father, both before and after the tragedy. Expanded noun groups add detail to writing, helping build characterisation:

The muscly, tanned guy who’d built me a two-storey tree house when I was a kid had been replaced by a

pale shell of a man who didn’t build anything. (p. 1)

Both noun groups include pre-modification (italics) and post-modification (underlined) of the head noun (bold):

The muscly, tanned

guy who’d built me a two-storey tree house when I was a kid had been replaced

a pale shell of a

man who didn’t build anything. (p. 1)

Students need to be shown how detail can be added before and after the noun.

Once students understand how these grammatical features operate in a text, they can begin to include them in their own writing to make it more sophisticated.

Modelled word solving (reading and viewing)

Modelling of new concepts is a common approach used during teaching. Explicit verbalisation, also known as think aloud, enables students to seemingly see inside the teacher’s mind to see how decisions are made (Fisher, Frey, Hattie, 2016, p.53).

Fisher and Frey (2009) have developed a three-part protocol that teachers can perform aloud. It involves:

- Looking inside the word or phrase for structural clues

- Looking outside the word or phrase for contextual clues

- Looking further outside the word or phrase for resources.

Teachers can practise this protocol, when they encounter new or challenging vocabulary. Students should then be encouraged to similarly rehearse this approach, in time internalising this vocabulary learning strategy.

Fisher and Frey’s (2009) three-part protocol in practice

Consider the following opinion piece about superheroes presented to a Year 9 class:

What fictional superheroes can tell us about devotion and why we believe in gods - by Thomas Swan & Jamin Halberstadt

The relentless supply of movies about superheroes and supervillains is difficult to ignore. Some people can’t get enough. Others hope to avoid them. But psychological researchers see a cultural phenomenon worthy of study.

Fictional characters with supernatural powers are often based on mythical gods and goddesses, fighting an ancient battle between good and evil with abilities that violate our intuitive expectations about the world.

In our recently published research, we asked 300 study participants to describe features of fictional supernatural beings and we compared them with features of the gods people worship. We found some striking differences that provide clues as to why some beings attract religious devotion, while others do not.

- From The Conversation, 30 September 2019

Teachers can display or give students copies of the text. As the teacher reads the text aloud, they interrupt their own reading of this text to ‘think aloud’ aspects of the text using Fisher and Frey’s (2009) three-part protocol:

- Looking inside the word or phrase for structural clues. For example, ‘super’ occurs in a number of words – identify the morphemes in each and highlight meaning of ‘super’ in each: supernatural – super + natur(e)+al; superheroes – super + hero + es; supervillains – super + villain + s

- Looking outside the word or phrase for contextual clues. For example, connection between ‘supernatural powers’ and ’abilities that violate our intuitive expectations about the world’. What might be our intuitive or reasonable expectations of what people can do? What kinds of powers might ‘supernatural’ characters have that violate or unsettle these expectations of ‘normal’ human capabilities?

- Looking further outside the word or phrase for resources. For example, ‘mythical gods and goddesses’. Who are some of the mythical gods and goddesses you are familiar with? What powers do they possess? Students research and report back. If students are unfamiliar with any mythical gods and goddesses, provide them with the names of some to research.

In this instance, students can see the thought process of the teacher as they read. Students could annotate the text with the teacher's comments as they think aloud. The teacher’s modelled word solving helps students understand and analyse textual language features and author word choices (VCELT440).

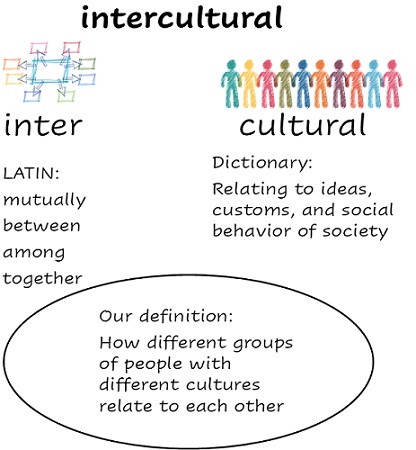

Joint construction of definitions when reading

Teachers may also use joint construction of definitions when reading. Rather than the teacher providing definitions, the teacher could stop at new or challenging words, and invite students to offer definitions.

This example of

joint construction in a Science classroom can be modified to support reading in English, as shown in the example below where a class has jointly negotiated the meaning of a key theme from 'The First Third' (Kostakis, 2013).

The class discussed the parts of the word, the Latin roots of the prefix (supported by

etymonline.com), and put the two meanings together to infer a new definition.

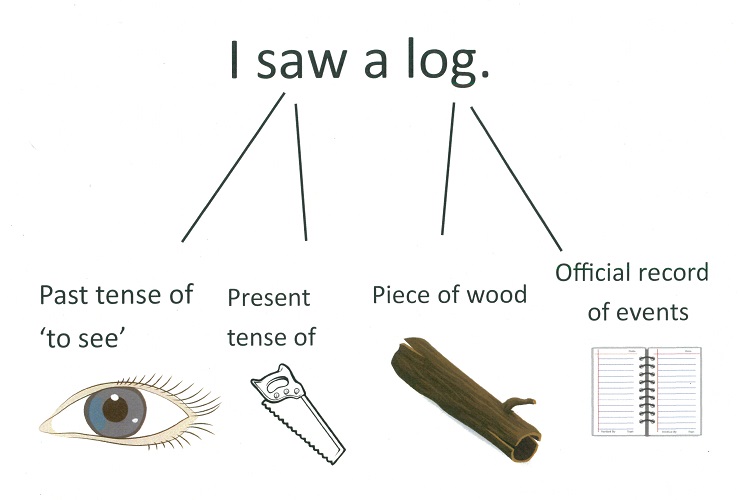

Semantic ambiguity instruction (reading and viewing, writing)

Semantic knowledge refers to meaning within language; semantic ambiguity refers to the notion that particular words can have multiple meanings. Teachers need to be aware of the semantic knowledge that students require in order to read the texts of English.

One challenge that students in English face is differentiating between the multiple meanings of words, especially homophones. Native speakers might not detect the ambiguity of some words when they appear in a sentence that offers narrow interpretations. However, lack of context or lack of repeated prior exposure to some semantically ambiguous terms may produce challenges for other groups, such as EAL/D students.

Consider the following sentence: “I saw a log”

- ‘Saw’ might refer to the past tense of ‘see’, or to the present tense of ‘to saw’ (to cut with a saw).

- ‘Log’ might refer to a piece of wood or an official record of events.

- This sentence has multiple meanings depending on how one interprets these two words.

Consider how the following words in English would be semantically ambiguous depending on where they are encountered in the English curriculum:

Act, atmosphere, character, drama, form, legend, meter, novel, plot, stress, tenor

Teaching students how to deal with words that have multiple meanings requires developing their metalinguistic awareness - that is, their ability to think and talk about language.

Zipke, Ehri and Cairns (2009) have developed a useful teaching technique to improve students’ abilities to detect and resolve their confusion around words that sound the same but are spelled differently or mean different things.

Their approach includes the following aspects:

Teaching multiple meanings

Students are taught that words can have more than one meaning by brainstorming words they know which fit this description and by sorting through word lists which include homophones.

Teaching multiple sentence meanings

Students are taught that sentences can also have multiple meanings by exploring ambiguous sentences, each accompanied by two illustrations representing different meanings.

The glasses fell to the floor and broke

The woman made the toast

Writing riddles

Lexical riddles (that is, riddles that draw on multiple word meanings) are introduced as a tool for exploring words that contain multiple meanings.

Students are supported to create their own riddles, brainstorming lists of words relating to their chosen topic and searching for relevant homophones. Students generate questions that relate to their identified homophones, including identifying answers that contain multiple meanings.

For example:

- Why did the skeleton go to the movies by herself? She had no body to go with.

- Why do spiders like baseball? They are good at catching flies.

- Why does Harry Potter go to school? To learn how to spell better.

In these examples, the homophones nobody, flies, and spell are the focus of student attention as they determine alternative meanings of these words.

Text reading and determining meaning

Students are presented with stories that contain word and sentence ambiguities. They are instructed to identify and explain the ambiguities encountered, including explaining the intended meaning and how they knew it.

Students are encouraged to brainstorm alternative meanings. These could be collected in a shared document as text study progresses.

These strategies are useful for supporting students to analyse and explain the way language features shape meaning and vary according to audience and purpose (VCELY379,

VCELY411).

Shared and modelled reading with think-alouds (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Shared and modelled reading are two ways teachers can support students’ reading comprehension.

Shared reading involves the students following the text and reading along with the teacher at different points. This strategy enables students to access texts that might otherwise be beyond their independent reading level (Winch & Holliday, 2012).

Modelled reading often occurs in a whole-class or small group situation. However, this approach is extended by incorporating ‘think-alouds’ where the teacher talks aloud their strategies to understand the content of the text being read. Doing so allows teachers to embed other comprehension strategies into their reading so that students can experience what good readers do.

Think-alouds in practice

The teacher will usually take the lead, working with the same text, sharing what they are doing, and asking for student input and suggestions.

- Before reading a text, the teacher emphasises what the goal of the reading is going to be.

- As the teacher conducts the read-aloud, they engage in some form of ‘think-aloud’ about the focus questions/concepts, pausing as they read in order to verbalise their thinking.

- An alternative is to have a student read the text and for the teacher (or students) to interject during natural breaks in reading in order to speak about the identified goals of the reading task.

Note that the content of the think-aloud can shift depending on the teaching focus. For example, Fisher, Frey and Lapp (2008, p.551) argue that modelled reading can serve at least four goals:

- Comprehension: allows for strategic and active moves to understand the text.

- Vocabulary: enables a focus on solving unknown words.

- Text structures: used to present information so that readers can see and predict the flow of information.

- Text features: reveals additional elements of the text to increase understanding of interest.

Modelled reading in practice

The following are examples of modelled reading using a novel (Will Kostakis’s 'The First Third') or an opinion piece from a newspaper (‘Sydney is the ideal WorldPride city’ in The Herald Sun).

Curriculum links have been supplied for Levels 7 and 8 for the worked samples, however the strategy could be easily adapted to support the Literacy strand in Levels 9 and 10 by changing the focus questions/concepts.

Introducing a novel: Prologue to 'The First Third' (Kostakis, 2013)

- Before reading the text, the teacher identifies key vocabulary to focus on and relates this to textual features to increase understanding and interest.

- In the case of 'The First Third', these vocabulary items could include themes (grief, stereotypes, generations), the many references to Greek cuisine (dolmades, moussaka), or key phrases that students might be unfamiliar with (bucket list, cultural traditions, family ties).

- The teacher provides a brief outline of the cultural aspects of the novel (i.e. the main character, Billy, is Greek) and one of the functions of the novel to represent ethnic diversity.

- The teacher may unpack further through discussion issues of identity associated with ethnicity, multiculturalism, and what it might mean to be ‘Australian’. This could occur before or after reading the text.

- The teacher lists the Greek words used in the prologue on the board and asks students to listen for these in the text, and to use surrounding text to construct a definition. Words might include:

- Yiayia, bouzouki, halloumi, moussaka, dolmades

- The teacher also asks students to focus on how each of the characters are introduced: Yiayia, Billy, Peter, Simon, mum.

- The teacher reads the text aloud and pauses at different points when they come across one of the focus words or characters. The teacher models their thinking by thinking-aloud. For example:

- Teacher reads: “You could practically hear the metallic twangs of the bouzouki.”

- Teacher thinks-aloud: “Bouzouki, that’s a new word. I wonder what that means. Let me read that sentence again. [Rereads sentence.] Metallic twangs, that’s something you’d say about playing a guitar or another string instrument. A bouzouki might be a string instrument.”

- Students can be asked to jointly construct the think-aloud, or to contribute to later think-alouds, so they can test their own comprehension and reading strategies.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCELY379,

VCELY411.

Introducing media articles

‘Australia is the ideal WorldPride city’, The Daily Telegraph, 18 October, 2018.

- Before reading the text, the teacher identifies text features to focus on and relates this to the features of the genre (opinion piece)

- Images (revellers celebrating gay pride)

- Heading (use of superlative, ‘ideal’)

- Bylines (appeal to emotion regarding overcoming fear)

- TEEL structure (Topic sentence, Evidence, Explanation, Link).

- The teacher leads a class discussion about the heading to have students predict what the central thesis of the opinion piece is.

- The teacher asks students to identify the topic sentence from each paragraph as they read the opinion piece aloud.

- Teacher reads the article aloud and pauses after each paragraph, thinking-aloud what the topic sentence might be and explaining how it relates to a central contention.

- Teacher thinks-aloud: “I might read that paragraph again, there were a lot of dates and cities mentioned. [Rereads paragraph.] Ok, so all of those cities and dates are examples or elaborations of the topic sentence of that paragraph. Let me go back and see what was written just before the cities are mentioned. [Mimes skimming text.] There it is; it’s the first sentence. [Rereads first sentence.] That’s the topic sentence. It’s about the fact that WorldPride is held every two years and is a global event that celebrates LGBTIQ issues on an international level. It sounds like WorldPride is a big deal.”

- Students can be asked to jointly construct the think-aloud, or contribute to later think-alouds, so they can test their own understanding of text structure in opinion pieces.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCELY379,

VCELY411,

VCELY413.

Word and concept sorts (reading and viewing)

Word and concept sorting strategies encourage learners to identify patterns to help make sense of new and important words.

Narrative based word-strategies

Narrative based word-sorting strategies (Allen, 2007; Hoyt, 2000) involve the teacher preparing a collection of important words from a story that students will be required to read.

Before reading the text, students are given the collection and required to arrange the words in the order that will support the telling of the story. This pre-reading prediction activity requires students to tell the story to a peer or the class using the ordered words. As the actual story is read, students reorder their words. This is subsequently followed by a post-reading ordering and retelling of the story, using the new arrangement of words.

For example, when reading 'Catching Teller Crow' (Kwaymullina and Kwaymullina, 2019) in a Year 7 class (VCELT385).

- Pre-reading

- The teacher prepares a list of words that are associated with the narrative.

For example, deceased, departed, discovered, haunted, investigated, solved, visited.

- Students are given the list and required to arrange the words in the order that they think will reflect the story.

- Students read their predicted stories to a peer or the class.

- During reading

- Students rearrange their words to reflect the narrative - Students may find that the words come to mean different things as they encounter twists in the narrative of 'Catching Teller Crow', and they move words such as ‘departed’ accordingly.

- Post-reading

- Students perform a final rearrangement.

- Students again read their final arrangements in the order that best supports the author’s intentions.

A similar activity can be used to develop students’ understanding of literary terms. Students can also sort words into concepts, grouping them together according to different categories of literary metalanguage.

Fisher, Frey and Hattie (2016) describe a concept sorting activity whereby students work in pairs to sort terms based on whether they are poetic or literary techniques, for example, onomatopoeia, simile, euphemism, or foreshadowing.

Working in pairs encourages students to process their thinking aloud as they sort the terms. Including terms that can be both literary and poetic techniques adds an extra level of complexity to the strategy.

The following word bank includes terminology used to study poetry and film in Year 9 (VCELY411,

VCELY444.

Students could use the table below to sort through the terms.

Word bank word lists

- Camera angle

- Couplet

- Cut

- Editing

- Elegy

- Framing

| - Haiku

- Jambic

- Lighting

- Metaphor

- Music

- Narrator

| - Protagonist

- Special effects

- Stanza

- Symbolism

- Themes

- Zoom

|

Word bank

| Words used in poetry analysis | Words used in film analysis | Words used in both |

|---|

| | |

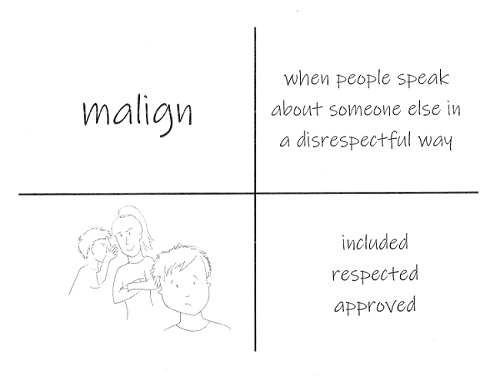

Word cards (writing)

Word cards provide multiple opportunities for learners to become familiar with new vocabulary. The exploration of new words via multiple representations can help highlight the key features and multiple meanings of new words, assisting students to understand them in more comprehensive ways.

The Frayer Method (Frayer, Frederick & Klausmeier, 1969) represents a one word card approach that involves using index cards to learn new words through various means.

- Students divide blank cards into four segments.

- In the top left corner, the student writes down the new word

- In the top right section, the student records their own definition of the word after hearing the teacher or a peer explain the term

- The bottom right section is where the student will describe the opposite meaning of the target word

- The bottom left section is used for the student to draw an image that represents the term.

The Frayer model in practice

When studying the poem ‘Son of Mine’ by Oodgeroo Noonuccal, the word ‘maligned’ may stand out as an unfamiliar term.

The example below is an illustration of how the Frayer model can be useful in building understanding of new terms (VCELY411,

VCELY444).

Teaching base words and word parts (morphemes) is another way to introduce new vocabulary to students. This

Science example of a parts card can be modified by English teachers.

References

Adoniou, M. (2016). Spelling it out: How words work and how to teach them. Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press.

Allen, J. (2007). Inside words. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2009). Background knowledge: The missing piece of the comprehension puzzle. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy, grades K-12: Implementing the practices that work best to accelerate student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Lapp, D. (2008). Shared readings: Modeling comprehension, vocabulary, text structures, and text features for older readers. The Reading Teacher, 61(7), 548–556.

Frayer, D. A., Fredrick, W. C., & Klausmeier, H. J. (1969). A schema for testing the level of concept mastery. Madison: Wisconsin University Research & Development Center for Cognitive Learning.

Hoyt, L. (2000). Snapshots: Literacy minilessons up close. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Munro, J. (2002). High Reliability Literacy Teaching Procedures: A means of fostering literacy learning across the curriculum. Idiom, 38(1), 23–31.

Myhill, D. (2018). Grammar as a meaning-making resource for improving writing. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 18, pp. 1–21.

Parkin, B., & Harper, H. (2019). Teaching with intent 2: a literature-based literacy teaching and learning. Marrickville: Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

Winch, G., Johnston, R., March, P., Ljungdahl, L., & Holliday, M. (2012). Literacy. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Zipke, M., Ehri, L. C., & Cairns, H. S. (2009). Using semantic ambiguity instruction to improve third graders’ metalinguistic awareness and reading comprehension: An experimental study. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(3), 300–321.