The language experience approach integrates speaking and listening, reading and writing through the development of a written text based on first hand experiences.

Through scaffolded talk, the teacher supports students to document experiences and ideas, using familiar and expanded vocabulary, modelling ways in which their thoughts and words can be written down and later read.

Procedure for the language experience approach

The experience

Typically, the language experience approach involves a shared experience such as everyday happenings, common school experiences, a classroom event or hands-on activity, excursions but can also include students’ personal experiences or ideas.

Spoken language

The teacher’s role in language experience is to support the student to recreate the experience orally as they:

- capitalise on students’ interest and experiences

- prompt the students to reflect on the experiences

- ask questions to elicit details about the experience through more explicit language

- help students to rehearse the ideas they will be writing about.

Creating the text

The text might be written by the teacher or by the student. As the writer, the teacher acts as a model, demonstrating how thought and words can be represented in writing as students dictate their ideas. Individual children might dictate a sentence, or a longer text might be written.

Alternatively, students will write their own texts. Here, the teacher can guide students’ writing, encouraging them to understand that what they think can be said, and what they say can be written down by them or others (Hill, 2012).

In the writing that occurs as part of the language experience approach, it can be helpful to remind the children that the writing produced will provide information for those who did not directly share the experience.

In that way, differences between spoken language and written language can be emphasised.

“How can we put that in writing for someone that wasn’t there?” is a question that might support children to create more elaborate, extended text.

As the texts written through the language experience approach reflect first hand experiences, the formats will vary – for example, charts, labels, captions, lists or genres such as recounts, procedures, information reports.

Drawing either before or after writing will often complement the written text. In her research into connections between drawing and writing, Mackenzie (2011) found that when emergent writers see drawing and writing as a unified meaning making system, more complex texts are created.

Reading

What is written can now be read. As the language experience texts are relevant to the students, the opportunity to read them aloud creates a positive experience and reinforces the reciprocity between reading and writing.

Texts that the students have produced based on their experiences, using familiar language make good early reading material which can be read chorally or individually.

Examples of the language experience approach in a foundation class

The following examples show how one Foundation teacher provided varied opportunities for her students to create texts using the language experience approach where:

- following discussion, writing about different topics and experiences is captured which can later be read about (for example, an excursion to the zoo, a visit by the fireman, an investigation of nocturnal animals)

- simple sentences using a repetitive structure are written for the students to illustrate and copy, supporting both reading and writing

- students are encouraged to write their own ideas, using compound or complex sentences and expanded noun groups

- the writing includes the labelling of a diagram.

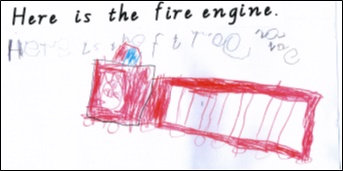

Example 1 – The fireman

After a visit to the school by the fireman, and extensive discussion of that experience, each child was provided with a series of simple sentences following a repetitive structure ‘Here is the …. (hose, ladder, fire engine).’ In the example below, the child copies the sentences and illustrates it

After a visit to the school by the fireman, and extensive discussion of that experience, each child was provided with a series of simple sentences following a repetitive structure ‘Here is the …. (hose, ladder, fire engine).’ In the example below, the child copies the sentences and illustrates it

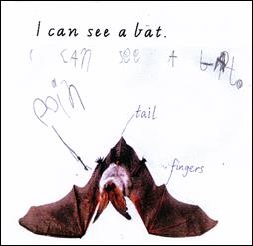

Example 2 – Nocturnal animals

As part of a direct experience and subsequent investigation of nocturnal animals, the students were provided with a simple structure following a repetitive structure, but were encouraged to extend the information based on their classroom research. Here, the student includes a labelled diagram of a bat.

As part of a direct experience and subsequent investigation of nocturnal animals, the students were provided with a simple structure following a repetitive structure, but were encouraged to extend the information based on their classroom research. Here, the student includes a labelled diagram of a bat.

The teacher has written two labels after asking the child ‘What do we call this part of a bat?’, and the child has added one label independently.

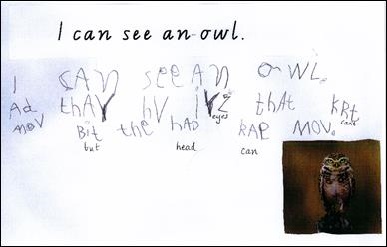

On another page in the booklet, the child copies the sentence supplied by the teacher, ‘I can see an owl’ but also extends the text by adding ‘And they have eyes that can’t move but the head can move’.

These additions to the simple base sentence provide an example of a rudimentary information report where the purpose is to inform. The child’s writing includes:

These additions to the simple base sentence provide an example of a rudimentary information report where the purpose is to inform. The child’s writing includes:

a compound sentence which includes the coordinating conjunction ‘but’ to contrast ideas (i.e. ‘And they have eyes that can’t move but the head can move’.) a relative clause to expand on the noun ‘eyes’ (i.e. eyes that can’t move) the present simple tense used in information reports simple punctuation (full stops). Example 3 – An excursion to the zoo

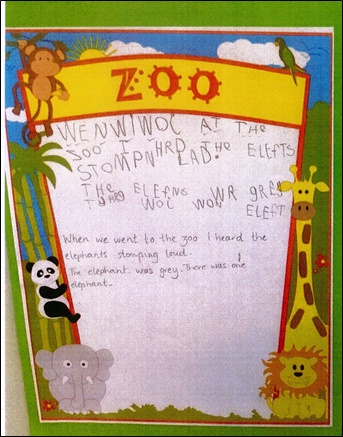

In this instance, the child’s writing includes:

a complex sentence ‘When we went to the zoo I heard the elephants stomping loud’ an embedded clause which expands on the noun ‘elephants’ (i.e. elephants stomping loud)simple past tense used to recount the experience and what was seen (e.g. went, heard, was)capital letters and full stops.

Because of the high degree of involvement the children have in the initial experience, subsequent discussion and creation of a written text, these texts often become favourite texts for children’s classroom reading.

Example 4 - A shared experience

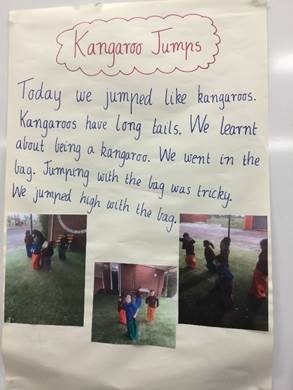

After participating in a shared experience of ‘jumping like kangaroos’, the teacher acted as scribe. The teacher provided prompts to support the students to recount and comment on their experience as well as to recall some of the information about kangaroos that they had been learning.

After participating in a shared experience of ‘jumping like kangaroos’, the teacher acted as scribe. The teacher provided prompts to support the students to recount and comment on their experience as well as to recall some of the information about kangaroos that they had been learning.

In this instance, words which students will later use in their own writing are used, such as kangaroos. High frequency words and conventions of written text such as capital letters and full stops also feature in the text.

For more examples, see:

Language experience unit of work for a foundation class

For an example of the language experience approach for EAL/D students, see:

Language experience unit for EAL/D students

Theory to practice

Lorraine Wilson advocated the importance of the language experience approach in ‘Write me a Sign’, published in 1979. A key message from this publication is that language is central to learning in all areas of the curriculum. Wilson also acknowledges the need for children to read published texts which open up possibilities of engaging with other people’s language and ideas as they become more experienced readers and writers.

Understanding the difference between spoken and written language is critical in the primary years of schooling (Christie, 2013). Hill (2012) states that language experience enables young literacy learners in particular to understand the difference between spoken and written language.

Importantly, children’s language is extended through interactions with an ‘expert other’, that is, the teacher. Through the expansion and extension of oral language based around experiences, students are supported to write about these experiences. These student-generated written texts then become texts the students read allowing the experience to be revisited.

While the language experiences approach benefits many kinds of learners, it is particularly beneficial for for English as an Additional Language or Dialect students.

For more information on the language experience approach and EAL/D students, see: Language experience approach and EAL/D students

References

Christie, F. (2013).

Writing development as a necessary dimension of language and literacy education.

Hill, S. (2012). Developing early literacy: Assessment and teaching (2nd ed.). South Yarra, Vic: Eleanor Curtain.

Mackenzie, N. (2011). From drawing to writing: What happens when you shift teaching priorities in the first months of school? Australian Journal of Language and literacy, 34 (3), 322-340.

Wilson, L. (1979). Write me a sign. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia.