Independent reading is an authentic and individualised practice that can support the explicit teaching undertaken during the whole group focus at the start of a reading lesson and provide opportunities for reflection at the lesson closure.

When students read independently, they are mindful of the explicit lesson they have just participated in, and draw on those skills to help them practise, read and understand text. After independent reading they are called on to share how those skills assisted their reading by giving an example or articulating their new knowledge or learning.

Independent reading is a practice which all students can successfully undertake as it can be differentiated for every student. Texts selected are usually at an easy level, i.e. 95 to 100% decoding accuracy rate.

Personal interest and literary texts also supplement independent reading material as reading for enjoyment and pleasure is highly engaging and has correlated links to reading achievement (Nodelman and Reimer, 2003; Thomson, Hillman and DeBortoli, 2013). For details, see:

Literature: Overview and Evidence Base

Independent reading takes the place of previous activity–based work centres that contained unrelated activities to keep students ‘busy’ whilst the teacher worked with individual or small groups of students. Whilst these activities may have been ‘fun’, they often had no relation to the learning intention (Hattie, 2009, p.163).

Conversely, independent reading is a practice that can be directly related to the learning intention and success criteria and can support the practise of new and reinforced strategies and knowledge.

Once independent reading time has been established, gradually introduce concurrent small group/individual student work. Discuss the role for students and for the teacher during this time so students know expectations. Display the expectations.

Independent reading and EAL/D learners

Independent reading in English and their home language helps EAL/D learners to build language and literacy skills in both languages (Schwinge, 2003). Strong home language literacy is a predictor of academic success for EAL/D students (Cummins, et al, 2006; de Courcy, Yue and Furusawa, 2008).

Include home language texts in students' independent reading boxes in the classroom, such as:

- home language realia

- multilingual library books

- books or stories translated by community members

- books or stories written by EAL/D learners

- versions of classroom texts summarised in home language.

For advice on text selection for EAL/D learners, see:

Literature

For advice on selecting texts in other languages, see:

Languages and Multicultural Education Resource Centre (LMERC)

Whole class-mini lesson

In this video, the teacher explicitly scaffolds whole class learning on reading through a mini lesson. The learning intention and success criteria are stated and explained and students are guided to use their new learning during the independent reading stage of the lesson.

Implementing independent reading

For independent reading to be successful in your classroom, teach the practice and allow time for the practice to be embedded.

Start early in the year and be consistent with the implementation so that all students know the expectations.

As it is a pivotal part of every reading lesson, it needs to be introduced explicitly.

Independent reading involves:

- the teacher modelling what independent reading looks like. This means the teacher reading independently alongside students to model ‘how to’

- developing some class protocols or expectations and displaying them on anchor charts/bookmarks (e.g. stay in your seat, read quietly, start to read straight away, read from your book box, enjoy reading)

- building up the time allotted for Independent reading. Start with 5 minutes. Keep a record of sustained and engaged reading times whilst introducing the practice. “Yesterday we read for 5 minutes, today I want everyone to read for 6 minutes without interruption”. Depending on the year level, independent reading times will vary (e.g. Foundation classes-10 to 15 minutes, Years 5 and 6-20 to 30 minutes).

- demonstrating to students after independent reading has concluded how they might show some evidence that they were actively thinking and using the strategy outlined in the lesson learning intention as they read. Teachers can:

- model how to use a Reading Response Book to draw or write about their new learning note something of interest on a post-it note

- stick post-it note to the relevant page in the text where that learning occurred

- consider a reading goal and prepare an example of how the use of that goal assisted successful reading.

This practice should only act as an adjunct to the priority of reading independently. The time taken on this task should only take up to 10 minutes and should be completed independently.

Student's role

- stay in your seat

- start to read straight away

- read quietly

- read from your book box

- use the learning intention to help me practise my reading

- enjoy reading

Teacher's role

- read with a group

- read with a student

- conference with a student

- teach students how to read

- talk about a book with a student or a group of students

- take a running record

The final part of the reading lesson provides time for students to show and articulate the thinking they have done when reading independently. Here the learning intention and success criteria are revisited and students have the opportunity to articulate their learning.

The final part of the reading lesson provides time for students to show and articulate the thinking they have done when reading independently. Here the learning intention and success criteria are revisited and students have the opportunity to articulate their learning.

Articulated learning example

(e.g. When I got to the word ‘dale’ on this page I did not know what it meant. I tried to think of synonyms that would make sense and would fit with the picture. I came up with ‘mountain’ first of all because of the picture. Afterwards, I checked with my iPad and found out it meant valley; the bit between the hills. Now I can go back and reread it and understand what it means).

Students also give the teacher feedback on whether they have achieved the success criteria. This information is useful for motivating students and allows the teacher to build on, modify or revise the learning intention in future lessons.

EAL/D students need to read books with engaging content that they can understand. If the text is too difficult (the student knows less than 95 per cent of the vocabulary and grammar) then they will not be able to read the text independently. Older students will spend too much time looking up the meaning of words in the dictionary which will detract from the reading (and enjoyment) of the text. It may be more appropriate for EAL/D students to re-read a text they previously found challenging to build confidence and fluency. However, it is important to model specific strategies that EAL/D students may use in independent reading when they encounter unfamiliar vocabulary, phrases or sentence structures.

To support EAL/D learners to read independently:

- teach and model how students can infer the meaning of new words based on the context, reading ahead, and other clues in the text

- establish a protocol where students record some unknown and/or interesting words to discuss with the teacher during a reading conference

- decide with students how and when they should use dictionaries or other resources in independent reading. Teach the process for looking up words in an English or bilingual dictionary if appropriate. Some options are:

- Before reading: students skim the text to identify new words. They check the meanings in a dictionary and note these down ready for independent reading

- During reading: when students encounter a new word, they make an educated guess about the meaning

- After reading: students look up a dictionary to confirm the accuracy of their inferences about new words they encountered during reading.

- teach and model some responses to independent reading that do not rely heavily on language, for example using drawing, storyboards, or graphic organisers

- teach and model using home languages to support independent reading. By drawing on their home languages, EAL/D students can think more deeply about their reading and make connections between existing and new knowledge. Some examples are:

- finding home language equivalents or translations for key ideas in the text

- summarising what they have read, orally or in writing

- talking to a same language peer about what they learnt from reading.

The benefits of independent reading apply whether students are reading in English or in their home language (Scwhinge, 2003).

Practising independent reading at home, whether in their home language or English, helps students learn language and literacy skills. Parents can engage in their children’s reading by:

- listening to their children read in English even if the parent does not understand English. The child can then translate or gloss the text in the home language. Both parent and child can discuss the book in their home language

- telling stories to their child in their home language or English

- keeping a collection of books at home, in the home language and English. These could be from the local library or owned by the family

- translating English books to the home language for the home or classroom library if they have the skills to

- reading books with their child in the home language or English, and talking about the books

- encouraging their child to read independently at home, and to discuss what they are reading.

To encourage parent engagement, see:

Speak to your child in the language you know best

For bilingual resources, see:

Languages and Multicultural Education Resource Centre (LMERC)

Text selection

'Enriching the print environments in classrooms has been shown to result in more reading' (Krashen, 2004, p. 58).

'Enriching the print environments in classrooms has been shown to result in more reading' (Krashen, 2004, p. 58).

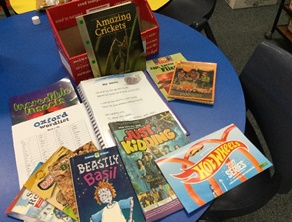

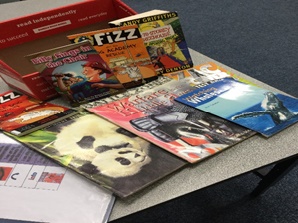

The selection of texts for independent reading can be drawn from a large repertoire depending on a student’s reading level and interest such as:

- guided reading texts

-

Language Experience books

Language Experience books - class-made books

- phonemic awareness rhymes and chants

- high frequency words/alphabet cards

- picture story books

- non-fiction texts

- Literature Circle texts

-

novels

novels - library books

- graphic novels

- comics

- magazines

- newspapers

- school newsletter.

For assistance, see:

Recommended independent reading texts for student book boxes-Foundation to Year 6 (docx - 467.11kb)

Recommended independent reading texts for student book boxes-Foundation to Year 6 (docx - 467.11kb)

Independent texts are usually housed in student book boxes or book bags. Each student is responsible for their own book box, however, it is up to the teacher to ensure that texts are changed regularly to promote interest and engagement.

Theory to practice

When reading independently students are exposed to new words in meaningful contexts.

The benefits of independent reading are wide and well researched:

- Stanovitch (1986) argues that reading is an important contributor to many language and cognitive skills, particularly vocabulary.

- Knowledge of vocabulary directly correlates to higher levels of achievement (Fisher, Frey and Hattie, 2016) and contributes to comprehension (Konza, 2010).

- Students who read daily for extended periods of time, encounter more new words, recycle known words and automatically recognise more high frequency words. De Courcy, Dooley, Jackson, Miller and Rushton (2012) argue that “students may need to encounter a new word up to 15 times to acquire it as part of their expressive vocabulary” (p. 6).

For more details, see:Rationale and Theory to Practice

Fluency is another important element supported through independent reading. When readers reread familiar texts or texts where the decoding requirement is minimalised, greater attention can be placed on building meaning (Konza, 2016). Student book boxes or book bags should reflect this requirement.

Fluency continues to develop as a reader engages with texts of expanding vocabulary and sophisticated concepts. Therefore, independent reading is a practice that continues to support readers throughout their learning.

As readers read texts fluently in independent reading, they:

- demonstrate accurate decoding skills (letters, sounds, words)

- maintain a steady rate for optimum understanding (e.g. too slow and the information will be forgotten, too fast and comprehension may not have time to develop)

- develop prosody which supports comprehension (e.g. expression, rhythm and phrasing).

For more details, see:

Fluency

Moreover, independent reading provides time for students to practise their reading goals. Students actually practise their reading goals by reading, not by activity-based tasks. Goals are determined as a result of explicit feedback from the teacher to each of their students.

Through goal setting students can “assimilate the language used by the teacher into their own self-talk”, which in turn contributes to their self-efficacy as learners (Fisher, Frey and Hattie, 2016, p. 101). Independent reading is a practice which supports students to develop and practise those goals while reading texts that are easy to decode, are familiar, or provide high levels of engagement.

By participating in independent reading, students can

- practise decoding and comprehension strategies

- practise and reinforce vocabulary (new, known and high-frequency words)

- practise reading for fluency (rate and prosody)

- determine the author’s purpose

- think critically about texts

- enjoy reading for extended periods of time.

References

Cummins, J., Bismilla, V., Cohen, S., Giampapa, F., & Leoni, L. (2006). Timelines and Lifelines: Rethinking Literacy Instruction in Multilingual Classrooms. Orbit, 36(1), 22–26.

De Courcy, M., Dooley, K., Jackson, R., Miller, J., Rushton, K. (2012). Teaching EAL/D learners in Australian classrooms, PETAA Paper 183, Primary Teaching Association Australia.

De Courcy, M., Yue, H., & Furusawa, J. (2008). Children’s Experiences of Multiple Script Literacy. In A. Mahboob & C. Lipovski (Eds.), Studies in applied linguistics and language learning (pp. 244–270). Newcastle upon Tine: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Duke, N.K. and Pearson, P.D. (2002). Effective reading practices for developing comprehension, In A.E. Farstrup & S.J. Samuels (Eds.), What Research has to say about reading instruction (3rd Ed) (pp.205-242). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Fisher, D., Frey, N. and Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for Literacy: Implementing practices that work best to accelerate student learning. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Guthrie, J.T. & Wigfield, A. (2000) ‘Engagement and Motivation in Reading’. In M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, New Jersey.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London and New York: Routledge

Konza, D. (August 2010). Understanding the Reading Process. Research into Practice: Literacy is everyone’s business, Government of South Australia: Literacy Secretariat

Konza, D. (2016). Understanding the reading process: The big six, In J. Scull and B. Raban (Eds.), Growing up literate: Australian literacy research for practice (pp.149 - 176). Hong Kong: Eleanor Curtain Publishing.

Krashen, S.D. (2004). The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research (2nd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Nodelman, P. & Reimer, M. (2003). The pleasures of children’s literature. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Schwinge, D. (2003). Enabling biliteracy: Using the continua of biliteracy to analyse curricular adaptations and elaborations. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Framework for Educational Policy, Research, and Practice in Multilingual Settings (pp. 278–295). Clevedon: Multilingual Matter.

Stanovitch, K.E. (1986). The Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences for individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly: 21 (pp. 360-407).

Thomson, S., Hillman, K. & De Bortoli, L. (2013). A teacher’s guide to PISA reading literacy. Camberwell, Vic: ACER.