Understanding students' language use is an important step when considering how to incorporate home languages into teaching and learning. There are various ways to gather this information, and student-based activities can also help to work towards learning objectives in both the EAL and English classroom. Each type of strategy comes with different strengths, and they can be used in combination. The strategies affirm students' language knowledge and background in the classroom.

Teachers discuss understanding students' language practices

Stories from the classroom

Parent surveys

Teachers: Daniel Thomas and Ryoki Fukaya, Huntingdale Primary School

Class type: Mainstream bilingual program – Japanese/English

Languages: Japanese, Hindi, Tagalog, Marathi, Vietnamese, Bengali, Malay, Mandarin, Cantonese

Dan and Ryoki had access to general information about their students' home languages, but they wanted to know more detail about their students' home language practices. The success of plurilingual strategies can be enhanced by knowing about students' background, and also by discovering how much parents are willing to be involved.

A survey was sent to all parents of students in Years 1 and 2 regarding their home languages and cultures. 90% of parents responded to the survey.

- What cultural background/s do you and your family identify with?

- Were you or someone in your household born outside of Australia?

- If yes, where were these people born?

- What languages do you speak in your house?

- Are you able to read and/or write in your home languages?

- What languages do you speak with your child?

- How consistently do you speak your home language with your child?

- Does your child understand or speak your home language/s?

- If yes, please give some detail about their ability in your home language.

- Is your child able to read and/or write in their home language?

- If yes, please give some details about their ability to read/write.

- Does your child attend a language school for their home language?

- What languages does your child have exposure to outside of the household? e.g. speaking with grandparents

- Would you be willing to share photos and stories with the class about where you grew up?

- Would you be willing to help students learn a sentence in your home language?

From their survey, Dan and Ryoki found out that parents mostly spoke in the home language to their children with some English, and some children were exposed to their home language by communicating with relatives and friends.

Data on literacy in the home language was also very important for the planning of plurilingual strategies. The teachers found that all the parents were literate in their home language, but this was not the case for many of the children. Even so, parents were generally willing to help students learn their home language. Just under half of the students were also learning in a community language school.

Requesting detailed information about home languages via a survey includes parents from the outset. It also indicates to the parents that the school values and supports home language maintenance.

"We've actually had two families say to us that these kids who had no interest in their home language have now started to ask parents about their home language and started to engage in the linguistic and the cultural elements of their homes, which is amazing."

This kind of survey is a useful activity for teachers because the findings can be surprising. Dan and Ryoki were most surprised by the number of parents who rated their children as having no or very basic literacy in the home language. They were able to take this into account when planning plurilingual strategies.

Student surveys

Teacher: Michelle Andrews, Preston North East Primary School

Class type: EAL students, withdrawal class

Ages: 9 to 11 years old

Languages: Tagalog, Somali, Mandarin, Telugu, Malayalam, Arabic, Vietnamese

EAL curriculum levels: B1 to B3

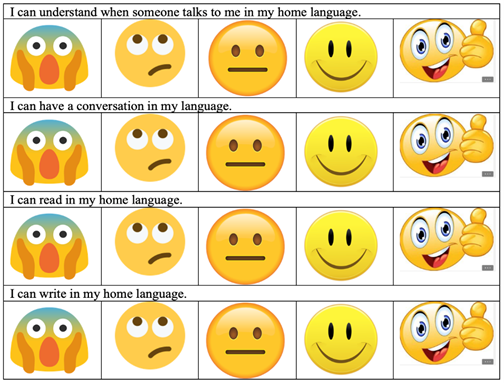

Michelle decided to learn about her students' language capabilities by conducting a survey with the students. She chose a simple diagram with five emoji faces and asked the students how confident they felt listening, speaking, reading and writing their home language. The survey results confirmed what she already suspected: that most of her students did not feel confident reading and writing in their home languages.

The survey led to class discussion about home languages and students were eager to demonstrate phrases in different languages. Michelle trialled the activity in another class, this time getting the students to choose a new colour for each language that they knew, including English. She reflected that this helped her understand comparative confidence in different languages.

"The survey gave me a good idea of how the students viewed their language capabilities in their home language and confirmed that most don't write or read their home language. Yet, they were keen to talk and demonstrate phrases in their home languages."

The student survey was a simple activity and Michelle found that it inspired the students to use their home languages to help their learning in class. She used it to plan further plurilingual activities.

Language portraits

Teacher: Hien Webb, Collingwood English Language School

Class type: EAL students

Ages: 11 to 14 years old

Languages: Assyrian, Arabic, Samoan

EAL curriculum levels: B1 to B3

Hien used different activities to find out about her students' language practices, and language portraits were among these activities. In language portraits, students represent their languages on a stylised body. The activity is particularly useful in seeing how students feel about the languages they use and how prominent these languages are in their lives.

Students drew language portraits that demonstrated the complexity of their language practices. Their experience with different languages was clear. They also showed the language of their heart, and sometimes drew more than one heart. Some students also showed English on the outside of their bodies, as a language that they were exposed to but had not yet internalised.

"I didn't realise that I've also got a lot of languages within me as well. When I reflected on that, I used the language portrait with the students. In a way that allowed me and allowed the students to really embrace the languages that they bring into the classroom. They can build on their languages to learn another language, which is English in this context."

This activity was a catalyst for discussion and was also a valuable point of departure for plurilingual strategies. It provided the opportunity to affirm the students' linguistic knowledge and experiences.

Further reading

Busch, B (2018). The language portrait in multilingualism research: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Urban Language & Literacies, Paper 236. The idea of using language portraits to represent language practices came from Brigitta Busch in 2006 following her research involving primary school children in the Netherlands.

Soares, C.T., Duarte, J., & Günther-van der Meij, M. (2020). 'Red is the colour of the heart': making young children's multilingualism visible through language portraits. Language and Education, 35(1), 22-41.

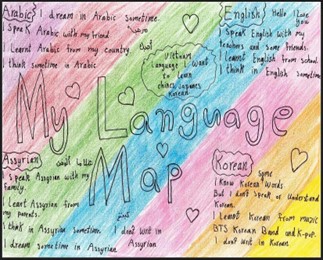

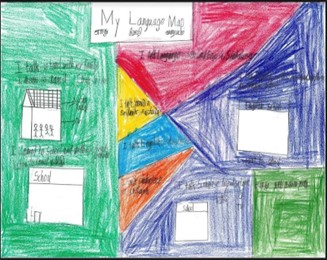

Language maps

Teacher: Antonia Ioannou, Collingwood English Language School

Class type: EAL students

Ages: 11 to 13 years old

Languages: Assyrian, Arabic, Vietnamese, Tamil

EAL curriculum levels: BL.1 to B2.2

Language maps offer another way to find out about students' language practices. These maps focus on contextual information about students' language practices: who they speak different languages to and where they speak them. Students can choose how to represent their langauges as a map. They can use writing or images or a mixture of both. Antonia decided to use language maps with her students as a way to introduce plurilingual strategies.

She learned about the students, and they also learned about each other. Sometimes it was clear on the language map that students knew how to read and write in their home language because they included it on the map. It was also clear that students' language practices were complex. For example, languages such as Assyrian or Tamil might be a family language but other languages, such as Arabic and Singhalese, might be used to talk to friends.

"Our first lesson was with the language maps which as a lesson in itself was really lovely. The students were really engaged with them. Even just the conversations that came out of doing the language maps were really beneficial and valuable. I think it's something I will continue to do because I found it was a good way to bring all of us together based on our differences in languages but also our common purpose to be at school and learn about each other and include everyone."

The language maps also helped Antonia to learn more about students in general. The language maps could provide information about student hobbies and activities connected to language, such as an interest in K-pop. This knowledge could be used to engage students in the classroom.

Further reading

D'Warte, J. (2013).

Pilot project: Reconceptualising English learners' language and literacy skills, practices and experiences. University of Western Sydney.

D'Warte, J. (2014).

Exploring linguistic repertoires: Multiple language use and multimodal literacy activity in five classrooms,

Australian Journal of Language and Literacy,

37 (1): 21-30.