The following strategies utilise existing texts, such as short narratives or familiar fairy tales, to support students to:

- redevelop characterisations

- examine archetypes

- develop critical literacy skills

- transform narrative into script.

Recreating characters from existing texts

The following strategy supports students to (re-)develop characterisations from existing texts. The strategy supports students to consider familiar characters and narratives from different perspectives, and therefore develop critical literacy skills. Critical literacy supports students to understand texts at deeper levels that see them think beyond the literal information on the page and to critically analyse the author’s message and how it is communicated (McLaughlin & DeVoogd, 2004, 2011).

- The teacher leads a discussion about archetypes in narratives. An archetype is a typical example of a character in narrative.

For example, fairy tale archetypes include

- the wicked witch

- the damsel in distress

- the handsome prince

- the evil villain.

- The teacher asks the students for further examples and to link these to narratives. Examples are noted on the board or poster paper.

- The teacher distributes and reads the existing text. The text may be a narrative familiar to students, for example a fairy tale, or an extract from a novel or a poem that they have studied in English. The example used in the steps described below is ‘Little Red Riding Hood.’ After the text has been read, the teacher asks the students to find the archetypes in the narrative, for example: the innocent girl, the old woman in the woods, the heroic stranger, the wild beast.

- The teacher leads a discussion about one of the characters to propose ways that the character might move, speak, use space, and appear. As the teacher leads the discussion, they ask for evidence from the text.

For example, for Little Red Riding Hood, the teacher and students might generate the following, which the teacher writes on the board:

Red Riding Hood, a naïve and kindly young girl from a decent family, often wanders absent-mindedly through the shadowy forest just outside the village. She is easily recognised by her cherry red hooded coat. She is politely spoken, although quite shy.

The teacher may also use the ‘Using embodied images to support speaking and writing’ strategy to support students to describe movement and performance.

- The teacher and students discuss the use of nouns (‘naïve and kindly young girl’), adjectives (‘shadowy’), verbs (‘wanders’) and adverbs (absent-mindedly) in the example and how these create a strong image of the character and the setting.

- Students form small groups and the teacher allocates an archetypal character from the existing text to each group. The teacher allocates 10 minutes for the student groups to draw on the existing narrative to describe how the character could be portrayed in a performance. The teacher asks the students to consider the character’s

- ways of moving (walk, gestures, posture, mannerisms)

- voice and vocal sounds (for example, tone of voice, loudness of pitch)

- use of space

- costume and props

- use of language (for example, childish, formal, impolite).

- The teacher asks the student groups to use their discussion to write a brief character description. The students are encouraged to use a range of nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, and hand-draw illustrations in their descriptions.

- The teacher asks each group to nominate

- one member to read the completed description to the class

- one member to ‘perform’ as the character, using movement, oral language, etc.

- After each group has presented their character, the teacher asks the students to ‘recreate’ their character using some or all the following prompts

- Change the character’s gender, for example, the woodcutter is now a woman, Red Riding Hood is a boy.

- Change the ‘archetype,’ for example, the wolf is no longer the villain, but is simply trying to exist in his natural environment of the forest, or the kindly grandmother is now a feared local politician.

- Change the setting, for example, the narrative is now set in contemporary Melbourne, your local town or neighbourhood or a different country and time.

- Using the prompts, the students rewrite/devise their modified character, following step 4 above. The teacher asks the students to consider how the changes in character and setting will affect the character’s

- ways of moving (walk, gestures, posture, mannerisms)

- voice and vocal sounds (for example, tone of voice, loudness of pitch)

- use of space

- costume and props

- use of language (for example, childish, formal, impolite).

- When the student groups have completed their new characterisations, the teacher asks two different students to:

- read the completed description to the class

- ‘perform’ as the character, using movement, oral language, etc.

- After the group presentations, the teacher asks each group to respond

- What did you change about your character?

- How did the character’s movements, voice, and presence change?

- Why did you make those choices?

- How does changing the time and setting alter the character?

- The teacher leads a final reflection of the process through whole class discussion

- What was the original purpose of fairy tales? What is the message conveyed by the original ‘Red Riding Hood’?

- How might the changes in the characters and setting change the narrative, its purpose and audience?

- Do the different representations provide us with diverse ways of viewing men and women, boys and girls, young and old people, humans, and creatures?

- How are family and other relationships represented in the original narrative and in by your revised characterisations?

- Who is missing from the narrative? How might diverse types of characters be included in an updated version of the narrative?

- The activities, discussion and reflection during this session may lead to the writing and performing of new versions of the entire narrative.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCADRE033,

VCADRE034,

VCADRD035,

VCADRD036,

VCADRE040,

VCADRE041,

VCADRD042.

Adapting existing texts into storyboards and scripts

The following strategy supports students to use existing texts as the foundation for developing storyboards and scripts.

-

Before reading the text, the teacher distributes copies of the extract to be used. The text may be a short narrative or an extract of a longer narrative. The example below is an extract adapted from a Japanese fairy tale, ‘The Story of Urashima Taro, the Fisher Lad'.

For the first few days in the kingdom under the sea, Urashima forgot about his parents; however, when he saw a woman calling for her son who had run away from her, Urashima realised that his parents would be missing him. He asked the Turtle Princess to take him home so that he could tell his family that he was safe and happy.

Before the Turtle Princess took Urashima home, she gave him a small wooden box as a gift. The Turtle Princess made Urashima promise that he would never open it. After Urashima promised, the Turtle Princess transformed into a turtle and carried him back through the sea to his home.

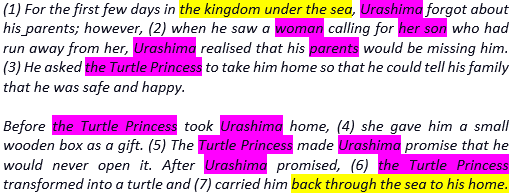

- The teacher explains to the students that they are to listen and follow the reading of the extract and identify by highlighting

- characters (pink)

- key events (numbered)

- details about the setting (yellow)

-

During reading, the students underline and highlight the aspects they have identified.

- After reading, the teacher and the students discuss their annotations (see below for example of annotated paragraphs).

- The teacher asks the students to use the numbered events to create a storyboard. The students are asked to use the language from the extract to create drawings of the event.

For example:

- The teacher leads a discussion about some of the more complex aspects of the story might be represented in the storyboard, for example:

- Urashima realising that his parents would be missing him (flashback, Urashima looking at a picture of his parents fondly)

- Urashima promising not to open the box (gesture of holding hand on heart).

- Using the storyboards and material from the extract, the teacher and students jointly construct dialogue (or a monologue) that might represent aspects of the story. For example:

He asked the Turtle Princess to take him home so that he could tell his family that he was safe and happy. (Original text)

Your Highness, I appreciate your hospitality here in your palace under the sea, but I know my family will be so worried about me. Do you think it would be possible to visit them to let them know I am well? (dialogue)

- Using their knowledge about the structures and features of a script, the original text and their storyboards, the students work in pairs to develop a short script.

- The students add more information about each scene onto the story board. The teacher encourages students to consider dramatic elements as well as dramatic conventions, including

- characters’ actions and gestures

- the tone, volume, and speed of spoken word

- costumes

- positioning of characters and objects

The teacher may remind students about how to use embodied images to support descriptive characterisation.

- Each pair performs their short script and teacher and students discuss similarities and differences in interpretations.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCADRE033,

VCADRE034,

VCADRD035,

VCADRD036,

VCADRP037,

VCADRE040,

VCADRE041,

VCADRD042,

VCADRD043,

VCADRP044.