Writing in the classroom should be reflective of the writing individuals do in their daily lives. Typically, we create written texts with a specific purpose and for an intended audience.

These considerations determine the form the writing will take and the language choices the writer makes.

Whatever the purpose, or whoever the intended audience, composing texts involves a sequenced process from the generation of initial ideas to the realisation of a finished product.

Teaching about the writing process is not the domain of any one particular approach to the teaching of writing.

Approaches such as the genre approach using the teaching and learning cycle, or the more process-oriented approach of the writing workshop, incorporate teaching about the writing process as students compose texts.

As noted by Christie (2016, n.p.), “As teachers and students together initiate writing activities in school, so too they engage in writing processes, shaping meanings, working towards purposes and creating different texts, or ‘products’”.

When composing considered pieces of writing that we intend others to read, this writing process usually follows a common structure:

- Planning and rehearsing: the generation, selection and sorting of ideas to write about, consideration of purpose and audience which will influence genre selection and organisation.

- Drafting or composing: the recording of ideas with attention to meaning making, grammar, spelling, punctuation and handwriting (or keyboarding).

- Revising: the revisiting of the text (often as a result of feedback from peers and/or the teacher) to improve and enhance the writing. This process of revising and composing may occur several times before the editing and proofreading stage.

- Editing and proofreading: the polishing of the draft in readiness for publication, which includes editing for spelling, text layout, grammar, capitalisation and punctuation.

- Publishing: the preparation of the text for sharing with an audience, with attention given to the form and style of the text.

It is this writing process—from planning to publication—that provides a template for thinking about supporting students as writers in the classroom.

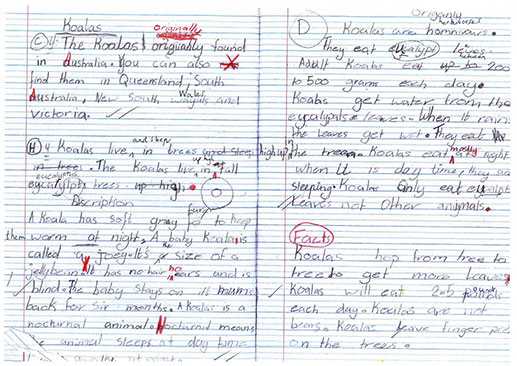

Examples of student's work.

Rationale for a focus on the writing process

The recognition of the writing process engages students in writing for specific personal or social purposes and alerts students to the conscious and considered creation of texts. It focuses their attention, even in the very early years of school, on the need to be attentive to authorial and secretarial aspects of writing, defined by Daffern and Mackenzie (2015) as embracing:

Authorial

- text structure

- sentence and grammatical structures

- vocabulary and word choice.

Secretarial

- spelling

- punctuation

- handwriting/legibility.

Early research around embedding the writing process into classroom practice (Graves, 1994; Myhill, Cremin, & Oliver, 2023) highlights high levels of student engagement with writing when their interests are legitimated and their topic choices are honoured.

Instituting a writing classroom that involves a writing process of planning, drafting or composing, revising or editing, and publishing, actively involves students in purposeful writing around which both their authorial and secretarial skills and understandings can develop.

Supporting EAL/D learners in the writing process

EAL/D students begin learning English at different points in their lives. Depending on their prior schooling experience, an EAL/D learner might need explicit instruction in either one or both authorial and secretarial aspects of writing. The type of scaffolding needed to support EAL/D students' writing is influenced by three factors:

- the student's age

- the student’s stage of literacy development in any languages

- their proficiency in English.

The following strategies are useful for early years EAL/D students who are new to formal written literacy or who are unfamiliar with the Latin script. Some of these can also be modified for older EAL/D students with limited English language proficiency and/or limited formal learning.

- Copying or tracing over a model sentence and drawing an appropriate image to match. Students unfamiliar with classroom practices might struggle to copy from the whiteboard from a distance. They might benefit from sitting closer to the whiteboard, or to copy directly from a personal whiteboard placed directly in front of them.

- Dictating a sentence for the teacher to scribe, and then copying the teacher's writing.

- Innovating on a focus sentence from a picture story book, e.g. Brown Bear, Brown Bear, what do you see? I see a (colour adjective) (animal) looking at me.

- Having a go' at spelling the words themselves, copying them from a bank of words supplied on a chart (e.g. colour words, animal words supported by pictures) or cut and paste the preferred words from a list provided.

- Providing a collection of sentence starters for students to use as they need to. Sample sentence stems for a recount might include: 'On the weekend ...', 'After we went to ...', 'The best thing was ...'

- Providing students with a cloze version of the modelled text where they supply only the missing elements. A cloze can allow the teacher to direct students’ attention to particular language features, for example, circumstance of time, or adjectives.

The Australian Institute for Teaching School Leadership (AITSL) website shows a teacher modelling

sentence structure to a Year 1 class with a number of EAL/D learners.

Explicit teaching and feedback

When teachers plan to be pro-active and interventionist in terms of supporting students’ writing, their role throughout the writing process can take the following forms:

1. Planning and rehearsing: “Getting started” on a piece of writing can be a challenge for many students, so the teacher’s role in supporting students at this planning stage might involve:

- brainstorming ideas for writing

- helping the students select a writing focus from a suite of possibilities

- modelling how initial ideas for writing might be noted (as pictures, mind maps, notes, etc.)

- jointly listing the key parts of the text. “As a class, let’s list as dot points what we need to include in this piece of writing.”

- thinking about the genre or text type that might be appropriate for different writing focuses

- talking to peers to generate ideas.

Supporting EAL/D learners to plan and rehearse their writing

For EAL/D students, planning and rehearsing can be enhanced by integrating their home languages, English and a range of multimodal modes:

- sequencing images, creating storyboards or using photographs

- talking with same-language peers in home language to generate ideas

- making voice recordings of storytelling or discussion

- creating mind maps or making notes in home language as well as English

- considering the intended audience of the writing. Are the readers likely to be bilingual, EAL/D learners or monolingual English readers?

Where students use visual images to map out the sequence of their text, they use the images to gradually build the language needed to encode the meaning they represent. Students do this by focusing on different aspects of the picture and producing the parts of speech necessary to form complete sentences.

With support, students label:

- the people or objects in the picture to generate the nouns or noun groups (e.g. a rabbit, a dog with brown fur)

- actions they can see (or perceive) in the picture to generate verbs or verb groups

- additional information to describe the circumstances around the activity. For example, to describe where an activity is happening, students generate prepositional phrases such as 'at my house', 'on the flower' or 'inside the cave'.

Students combine these three elements to produce sentences about each image, e.g. My friend plays at my house. Students might begin by writing one sentence for each image and move to writing a short paragraph about each image. If students cannot annotate the image in English, they need to be given this vocabulary from a peer, the teacher or with the assistance of a bilingual dictionary.

2. Drafting or composing: Students need support for recording ideas in an initial draft. Teacher modelling or joint text construction can be very supportive for students at this point. This might involve:

- modelling how to convert ideas or speech to written text. So, the teacher engaging in a ‘think-aloud protocol’ might be of benefit, such as, “I need to remember that I am writing this for people who were not there when the events happened. So, I’ll need to include information like where the action took place and who was there. Let’s see—how will I start …”

- enlisting student support to collaboratively construct a text (or sections of a text). “Who has a suggestion for what important details we need to add here?”

- demonstrating risk taking strategies in undertaking ambitious writing. “I’m not sure how to spell extrovert—but it’s a perfect word to use here. I’ll have a go at it, underline it and check the spelling later. I need to get my ideas down first.”

- making connections from texts read to those being drafted. “Remember how E.B. White started Charlotte’s Web with dialogue? Why don’t you try that in your narratives?”

- explicitly drawing attention to linguistic structures and features of different text types. “Remember, this is a recount. It happened in the past, so we need to use past tense verbs.”

Supporting EAL/D learners to draft and compose their text

It is useful for EAL/D students to also have a model or structure to prompt their writing during the drafting or composing stage. Some examples include using:

- headings, questions or picture prompts showing the stages of the text

- graphic organiser showing the key elements of the text type can be used as a planning tool

- a Venn diagram to show the similarities and differences between a new genre and a previously learned genre.

Students’ home languages can also support fluent writing. For example, if students are ‘stuck’ on a word or phrase, they can note down the meaning or a synonym in their home language, and come back later to check or translate it. They can also write an initial version of the text in their home language to 'get their ideas down' and then focus on their expression once the content is set.

Writing a longer text can place a high cognitive load on EAL/D students as they make connections and draw on new knowledge of content, language and text. It may be appropriate to break the writing task into smaller chunks. For example, students write, workshop and receive feedback on just the introductory stage of the text before proceeding with the next stage. This has the advantage of clarifying correct language use in one stage, before it is practised and reinforced throughout the text.

ABC Education Literacy Mini Lessons

The Department collaborated with ABC Education to create a series of videos. All 16 mini lessons based on content from the Literacy Teaching Toolkit are available on the ABC Education literacy mini lessons page.

3. Revising: As individuals, with classroom peers and with the teacher (incidentally or at a more formal conference), students need to be actively rereading over written drafts with a focus on meaning and form. Important considerations here are whether the text makes sense, ideas are presented clearly and sequentially. Actions might include:

- expanding noun groups to provide more detail

- removing redundant or unimportant information to make the piece clearer

- focusing on more precise, technical language word choice

- using connectives to improve transitions between paragraphs.

Supporting EAL/D learners to revise their writing

For EAL/D students, significant language learning occurs during the revising and editing process. This includes learning to distinguish between social English choices and literate or academic language choices (e.g. We found out about how clouds form versus Our investigations into cloud formation showed ...).

Since EAL/D students are still learning English, their written work may contain many grammatical and/or spelling errors and non-standard forms. Teachers and learners need to be strategic in their revision strategies and not attempt to correct or modify everything. For example, if the target text is a biography, past tense is a crucial grammatical feature. Focusing students' attention on using past tense forms of verbs they have learnt in their writing of a biography would be a worthwhile starting point. There may be scope for teachers to address related features such as word choice (e.g. repeated use of 'went') at the same time.

While correcting students’ grammar and spelling is important, EAL/D learners also need support and feedback around content and making meaning. The revision stage could also be viewed as an opportunity to focus solely on the ideas of the written piece such as the quality of arguments, and leave the language component to the editing phase.

As with all learners, developing strategies and tools for revising writing will be useful in the long term. These can include:

4. Editing: Students edit their texts focusing on conventions (spelling and punctuation) to ensure they are incorporated correctly and in ways that will assist the reader. The teacher’s role in supporting students to edit their writing might be:

- ensuring that if the writer is mindful of the reader at all times, making visible the proofreading strategies writers need to enact. “I’m not sure about my spelling of that word extrovert. Let me say it slowly in syllables: ex-tro-vert. What sounds do I hear? How might I record them? Does it look right? I better check using a dictionary or spell check”

- orchestrating a peer-review process. “When you share your written pieces with each other, always begin with positive feedback. Two stars and a wish is a good approach—offer two compliments, then a constructive suggestion”

- modelling word substitution. “Instead of saying ‘We got bored’, what could we write? What’s a better word than got? ‘We became … what … disinterested …”

Supporting EAL/D learners to edit their writing

Helping EAL/D students develop editing strategies will support them in future writing tasks. Useful strategies might include:

- reading aloud to identify tricky spelling or expression

- using bilingual dictionaries or translators to check spelling and meaning

- focusing teacher feedback on a small number of features (3-4) with each piece of writing. These may be features that were explicitly taught in class, or features that are part of the student’s personal learning goals

- EAL/D students having additional learning goals in relation to their writing. For example, learning how to use plurals correctly in English. This might include double checking that nouns marked as plural are countable nouns, e.g. He has grey hairs and many wrinkles vs He has grey hair and many wrinkles, irregular plural forms (tooths vs teeth), or non-marking of a plural (She bought two banana).

For more information, see:

The writing workshop

5. Publishing: The final form of a written piece might be a digital publication, a paper-based text, an audio-recording or podcast, among many options. Rich models of published texts serve as exemplar texts that students might strive to emulate. So, the teacher’s role here can be around:

- modelling and deconstructing existing texts as mentor texts for students: these might be web pages, picture books, graphic novels, podcasts, pamphlets, information texts, etc. Salient features of these texts should be noted for students to appropriate and adapt.

- supporting students’ publishing by recognising different strengths and talents in the classroom: the students who have an excellent eye for layout, are talented calligraphers, adept on the keyboard, etc.

- encouraging students to offer feedback on published pieces of classroom writing. This can include students reflecting on their own successes. “Was there something you did with this publication that you’d never done before?”

- celebrating successes and the mastery of new skills around text creation. This can take the form of special classroom celebrations (as mentioned earlier) but can also take the form of ongoing feedback. “Can I just share some really amazing things I’m noticing as you are all working away on your publications?”

Publishing EAL/D learners’ writing

Publishing EAL/D students’ writing is an opportunity to engage a wider audience by:

- inviting family and community members to read or listen and give feedback

- engaging family members who can provide written or spoken translations of students’ writing

- developing a classroom library of multilingual and multicultural student texts to sit alongside published work by international authors or multilingual Australians (e.g. Anh Do, Gabrielle Wang).

If students are writing for a bilingual audience, or for other EAL/D learners, some useful features of a publication might include:

- speech bubbles or captions in home language

- a glossary or in-text translations of key words

- a translation of the text, or parts of it

- a blurb or synopsis of the text (in home language, English or both) providing a summary

- audio recordings of the writing in home language, English or additional languages.

The students’ role in the writing process

The writing classroom needs to be a supportive environment for students to:

- experiment

- innovate

- attempt new and different forms of writing.

So, while mindfulness of an audience necessitates attention to conventions around grammar, spelling and punctuation, students must feel they have licence to learn through a process of trial and error.

Newkirk and Kittle (2013), reflecting on the legacy of Donald Graves, note that a successful writing classroom is one where students feel a sense of:

Students need to know that their writing choices will be respected, and that feedback will be offered respectfully and sensitively. In addition to these rights, they also need to know that they have responsibilities in what they write—and that sensitivity to the reality of student diversity needs to be carefully considered as students embark on writing that will entertain, inform and engage.

Grammar

In this video, the teacher explicitly demonstrates how to expand noun groups to include pre and post modification of the noun. This example shows a whole group mini lesson and differentiated small group learning.

References

Christie, F. (2016). Writing development as a necessary dimension of language and literacy education.

PETAA Project 40 essay 3

Daffern, T. & Mackenzie, N. (2015). Building strong writers: creating a balance between the authorial and secretarial elements of writing. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years, (1), 23-32.

Graves, D.H. (1994). A fresh look at writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Myhill, D., Cremin ,T.,& Oliver, L. (2023) Writing as a craft: Re-considering teacher subject content knowledge for teaching writing, Research Papers in Education, 38:3, 403-425, DOI: 10.1080/02671522.2021.1977376

Newkirk, T & Kittle, P., Eds. (2013). Children want to write: Donald Graves and the revolution in children’s writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.